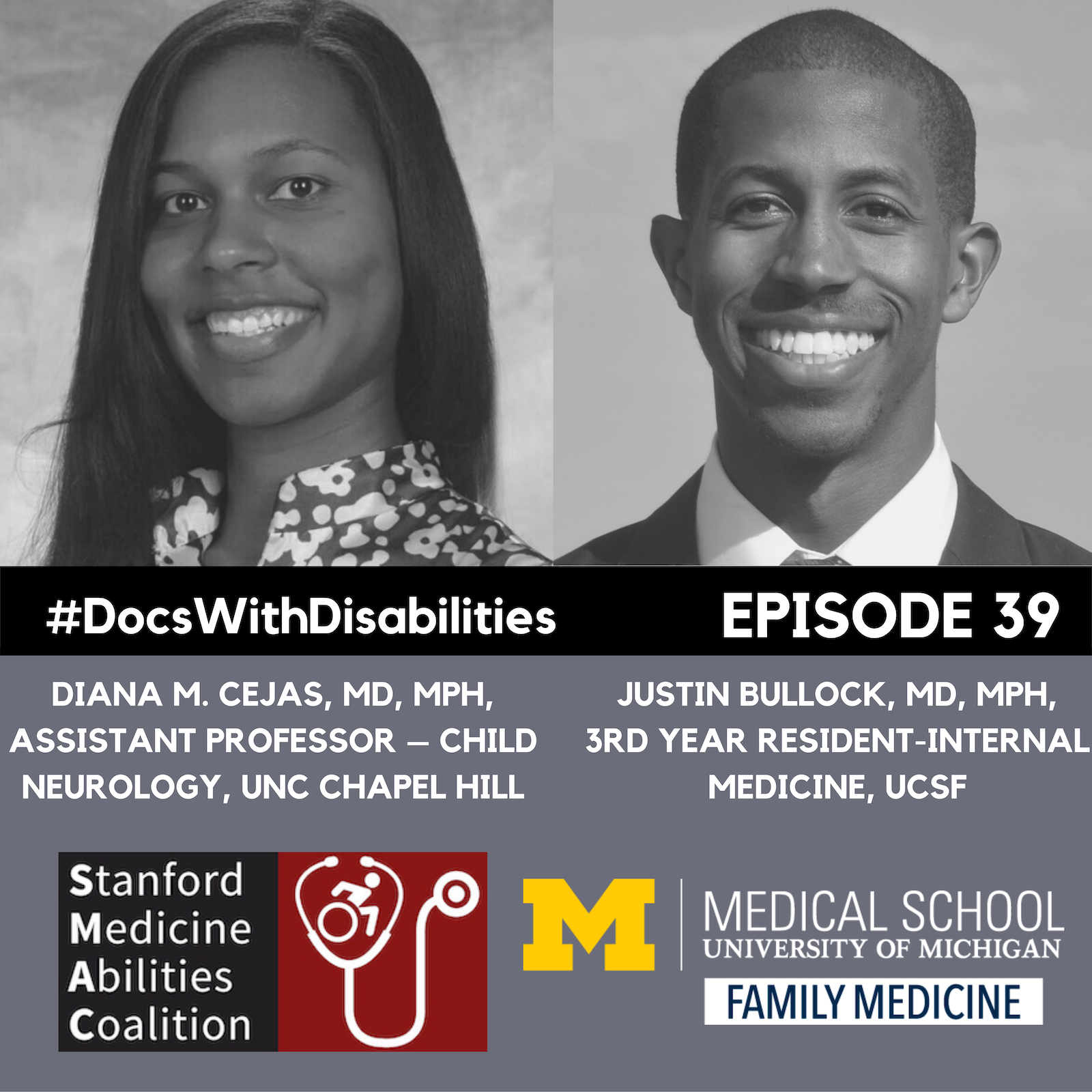

In the third installment in our series on BIPOC voices we have a two-part interview with Dr. Diana Cejas and Dr. Justin Bullock who talk about the intersection between disability and race, their experiences as black physicians with disabilities, what it means to be a good ally, and the value of mentorship, sponsorship, and community throughout one’s career.

Transcript Part 1

Peter Poullos:

Doctors with disabilities exist in small but impactful numbers. How do they navigate their journey? What are the challenges? What are the benefits to patients and to their peers? And what can we learn from their experiences? Join us as we explore the stories of doctors, PAs, nurses, OTs, PTs, pharmacists, dentists, and other health professionals with disabilities. We'll also be interviewing the researchers and policymakers that drive medicine forward towards real equity and inclusion. I am Peter Poullos, and I am thrilled to bring you the Docs With Disabilities Podcast.

Sofia Schlozman:

Hello and welcome back to the Docs with Disabilities podcast. Today we bring you the third installment in our series on BIPOC voices with a two-part interview with Dr. Diana Cejas and Dr. Justin Bullock. Both of these guests have been featured on our podcast before, and we highly recommend that you check out their previous interviews if you have not already done. Today, Dr. Bullock and Dr. Cejas return to the podcast to talk specifically about the intersection between disability and race. Throughout this two-part series, they discuss their experiences as black physicians with disabilities, what it means to be a good ally, and the value of mentorship, sponsorship, and community throughout one’s career. We begin with an introduction from both guests.

Diana Cejas:

My name is Diana Cejas, my pronouns are she, her, hers. I am an assistant professor of neurology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and faculty of the Carolina Institute for Developmental Disabilities. So that means that I primarily work with children, adolescents, and young adults with any kind of neurodevelopmental disability, and other kinds of neurological conditions, and usually complex behavioral conditions as well. I say that I'm in the world of disability full time, because I'm also a cancer survivor, and stroke survivor, and pretty much all of my clinical work, research, advocacy, and writing that I do as well is somewhere under that umbrella.

Peter Poullos:

Dr Bullock?

Justin Bullock:

My name is Justin, I am a third year resident in internal medicine at UCSF originally from Detroit, Michigan. I always loved getting to join Dr. Cejas, we co-exist in a lot of spaces and I guess my connection to the world of disability is from being bipolar, and I identify as someone who is sometimes disabled. And I am very passionate about sort of challenging a lot of common sort of stereotypes about folks with mental illnesses, and I think particularly something that I've been thinking about recently is sort of the, the some of the unique aspects of identifying but as having bipolar disorder and I guess the concern of having a psychotic condition which I think is, makes it in some ways unique from some of the other mental illnesses.

Peter Poullos:

I feel this special affinity for Justin, because I did the same residency program that he is doing right now.

How is it for you now that you're an upper-level resident?

Justin Bullock:

Yeah. So, my residency time has been challenging. I certainly struggled as an intern had a period where I was sort of did a lot of nights and days, and nights and days, and became hypomanic, and then quite depressed, and attempted suicide, and was hospitalized, and then after that really faced a lot of, sort of stigma, and difficulty getting back to work, and the rest of my residency experience is really framed through my enduring experiences. It's very, it's a very complicated thing. Like right now I feel, I feel good. It's I'm, I'm much happier, in a much better place than I was before and obviously we'll talk about the, this many aspects of this today. But residency is challenging, and I, and in general I think it's abusive.

Peter Poullos:

Well, I should also mention that this is 20 years in my rearview mirror, so (laughs) maybe it seems a lot better than it actually was.

Justin Bullock:

(laughs) it, it definitely is better than it was when I was an intern and I still think we have a long way to go.

Peter Poullos:

We have a long way to go, I agree in so many ways. So, I wanted to just ask you guys some general questions, and you guys feel free to riff off each other, and expand on these as you see fit. But what does it mean to be a Black doctor with a disability?

Diana Cejas:

Oh, I think I think the first thing that comes to mind is that, I mean, certainly something that a lot of people of color, a lot of Black doctors, a lot of really doctors that belong to any marginalized group, and one of the things that we talk about is being hyper visible, and invisible all at once. I think thinking about being a Black doctor with disabilities one of the first things is that people just don't think that we exist people are often surprised more than I would like to admit. When they realize that I am the physician and if I come in, and also I'm showing any of my little stroke-y symptoms, or talking about my experiences with my own medical conditions, with my disabilities, it's like, "Wow, I had no idea that you weren't... Like people like you were even working in medicine." And it's like, "Yeah I'm here, I'm trying to do my job."

So I think that, that that kind of invisibility it, it can really just lead to people not really understanding what your specific needs are and that's whether you're in training I think, but that's even when you come to a faculty position, and I think that a lot of people seem to think that especially if you are a doctor, you are Black, you are disabled, you are whatever else, one of the marginalized groups you belong to, I think that they think that because of your status, because of your degrees, your board certification, or whatever, you have somehow quote unquote overcome certain struggles, and things don't necessarily apply to you.

It's like, you're right there but people just kind of don't think that you exist, but then somehow you're some kind of superhero who's doing all this amazing work, so you don't need any help, so, and you can't be struggling. So, it's a weird, a very strange place to be in.

Justin Bullock:

I agree with all that, and I guess my two things I recently heard someone describe a phenomenon which is called the pet to threat phenomenon, and Dr. Kate Lupton in a talk, and basically it's this idea that often times and, I'll speak, I'll speak for myself, I certainly have been very widely sort of visible as I am saying, publicized by my institution. I've been on so many like institutional brochures, my mom always gets upset, she's like, "Do they not have any other Black people?", and like really marketed, and for me I'm, I also write about being bipolar, and it's something that when, when you have a big publication is looked upon very favorably, and when you begin to sort of unearth the problems within the institution related to holding those marginalized identities, then you'd go from the pet to the threat, and I think that, that is a very strongly Black and disabled person experience.

And the other thing I will say is I actually do see a lot of power and strength in existing in the spaces that we do and like how meaningful it is to my community. And I actually recently was talking with an undergrad who had like heard my Docs With Disabilities Podcast, and had like reached out to me, and basically said like, "I didn't even know like, that it was possible that like, someone like you could exist" and in that way, I took it from a place of like power, and like, and like strength. So, I think, I think it, I think it is this interesting juxtaposition of good feelings (laughs) and bad feelings.

Peter Poullos:

Gosh, this, that idea of invisibility is something that's like so foreign to me. I feel like I can't go anywhere, because with my crutches, and my Segway, and not have like the whole room following me. I guess this is not really, that's not the kind of invisibility you're talking about though you're more referring to like your existence, and I'm referring more to like my physical presence. So, I mean, how, how do your disability, identity, and African-American, or Black identity like intersect in other ways? Or can you talk more about how this is discussed like commonly in the literature, or in the press?

Justin Bullock:

Yeah. So first I'll start in the period that I had challenges with my institution, and went through this process, that's, that I've kind of spoke in other forms spoken a lot about fitness for duty basically where my fitness for like serving as a physician was questioned because of my bipolar disorder, despite having no concerns in the workplace. And one of the things that was happening was as this was ongoing, I was getting extremely, extremely angry. And one, as a Black person in like academia at UCSF like, I'm not really allowed to get angry because it's very threatening to people. and also my anger was, I'm 100% sure attributed to me being manic, and everyone's like, "Oh, he's just manic, he doesn't he's like being irrational, and like impulsive and angry because of his bipolar disorder." And for me it's like, "No I'm, I'm angry because this is actually unfair, and you're actually harming me."

And as I went through these processes, there was not a single Black person in any of these spaces. And so for me it's like, I knew that there was no one who was advocating for me who understood my experience. So, I think that's one way as a patient I've had like inpatient psychiatrists who've told my outpatient doctors that I wasn't taking my medications, and that my like levels were undetectable when I came to the hospital, with, which like upon review of my records is false, and my own providers like believed the inpatient providers and not me and for me that was very harmful. And, and I think that's more in the bipolar maybe? I, I attribute that more to the bipolar than like them attributing it to for me being mistrustful because of my mental illness. This is very complex because there's, I've never had a psychiatrist, or therapist who looks like me, ever and that changes, and like me being Black is a huge part of my life experience.

Diana Cejas:

I feel like something that you are maybe alluding to, but not, not saying out loud just yet, it's like, it's impossible to separate the two. "I am disabled, I am Black, I am both at the same time, just as I am, whatever other identities you wanna put together, all of those exist in me at once." And even in thinking about how ... I was talking with someone a couple of weeks ago about another lecture that I'm planning to give where I'm in there with my dis- disability and diversity hat on, and specifically they've asked me to do some talking about a certain topic, and they're like, "Well, we want you to focus more on disability right now, but maybe not so much about race and ethnicity." And I'm like, "But you're, if you're asking me to talk about my personal stories, my personal experiences as, as a patient with medicine, I, I cannot divorce those two things. Because can I say that the treatment that I've received from other physicians is due to the fact that I'm Black? Is it due to the fact that I have these disabilities? Is it due to the fact that I am a woman? Is it due to the fact that I'm Latina?” I have no idea, because all of those things coexist to me at once.

And the way that I respond to, or the way that other people respond to me especially when where either it's me as the patient, or me as the physician is completely shaped by the fact that I'm kind of all these things at once. And Just- Just- Justin talking about the whole not being allowed to be angry, thank goodness. I am a Black woman, I am six foot tall, and I have natural hair. So, it's like, I cannot come into a space without consciously thinking about how I am coming in, how I'm going to be perceived. If I'm gonna make somebody cry and how exactly it is that I have to carry myself in order to be able to get my point across and not be seen as the angry, confrontational just evil person. If you don't have this life experience, you might not necessarily know how much work it takes just to be able to kind of read a situation and figure out how you can make yourself as non-threatening as possible, and then go about the rest of your business.

And this is on top of the fact that especially if it's a day when I'm having like a lot of chronic pain, or maybe a day when I have follow-up appointments, or something else that's going on with my health, I'm having to do this additional work on top of all of that. So again, it's not just that I'm Black, and I'm existing in this space, and academics, or even in this space is coming as a patient, it's like I'm having to do all the rest of this work too, and that's just I think... there's been a lot more people paying attention to how we're trying to be more intersectional in their approach when it comes to things like burnout, when it comes to things like supporting people in academic medicine. But not, not enough, cause people aren't thinking about how much additional work there is to be done and additional work that you have to do just to exist as a person with all of these different identities.

Justin Bullock:

I agree so much about this, that I think people feel that these identities can separate, that you can separate them, and it's been really fascinating the last two years or so, because like, it's kind of like the rage to be like pro-Black and like challenge anti-Blackness, and all these things and something that... So, I'm a very active tweeter for those of you out there and I, I'm kind of like... I tweet about my life, like just the day-to-day, and when like all the stuff related to me being bipolar was happening, I was tweeting very aggressively, and like I think I was showing that I was very distressed and a lot of people outside of my institution recognized that, but my institution didn't respond to that. And now, if I tweet anything about like, "A patient called me the n-word." Which has happened, or like "The police stopped me in the hospital." Which also has happened.

Then people, like highest people within the institution like vice chancellors reach out to me, like chief of staff at the hospitals, like all these things because now like being, being like pro-Black, being against like anti-Blackness is like, is, is in vogue, and in a lot of ways, it actually is even more insulting to me, to my past experiences when I had, in my opinion, sort of expressed much more distress.

Like I, I obviously do not like being called (laughs) the n-word by patients I would prefer that not happen, but yeah, I think it's, to me it feels disingenuous because it feels like people are just doing it because it's kind of the thing to do now, and not because they actually care about challenging the power structures that exist.

Diana Cejas:

I am definitely feeling that, thinking about all these diversity, equity, and inclusion activities that really kicked up last summer, and that have... I, I mean, one of the things I've been saying, because I will freely admit, I am involved with several diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives, because part of me is like, "Well, if I'm not out here work, doing some of this work, who's gonna do it?", especially when I'm thinking about these things through this intersectional lens, and thinking about other people who might have these various identities, like, there needs to be someone in the room who looks like me, so, "Hey, here I am, I'm trying to do the work, I'm trying to see if we can make things better." But still, thinking about even when I first got started with some, some, some of these initiatives, last summer I was just sitting there, and the pessimist within me was like, "Okay, so when are y'all gonna get tired of this? And us move on to something different?"

And when I would say that and I've tried to be as frank about it as I could in some of these meetings, and be like, "This is something that I am worried about." Because right now everybody is thinking about race, everybody is thinking about how to be anti-racist, everybody is having their book clubs, everybody is having all these other kinds of initiatives. But how long is this gonna last? Because it's like, I've been in this body and I will be this person, and I will be this race for the rest of my entire life, so I'm gonna be thinking about these things for my entire life and have been since I was a very small child.

I, sometimes it just feels like, if there's not an active ongoing enthusiastic re- review, and enthusiastic involvement, and like, and commitment to the, that kinds of stuff. And it just kind of feels like it's, you're like this flash in the pan, like, "Wow, let's be excited about Black doctors right now." But are you really gonna care in two years? Three years? Or when the next thing happens? Or is this just kind of the thing to do right now? Like, "Well, are you really investing in us or not?"

Peter Poullos:

To me I'm 49 years old, and so I'm not old, but I'm not young. I've never really felt like any moment really feels like this moment, in terms of like, white people being on board with supporting black people. Like, a lot of the bad stuff that happened where the black community was rightfully outraged, like Rodney King, for example, or there were like... Or events that pitted the white and black communities against one another like the O.J. verdict, for example. It felt like that- the white people were not, like, having that at all.

Peter Poullos: I'm not in any way denying your experience, I'm just saying that this feels a little bit different. I'm also, like you, curious to see if it lasts, and hope-hoping that the effort is sustained. I didn't realize, in fact, how much white privilege I had, until recently. Learning about that since our book clubs have been taking place, and our YouTube videos. I've learned so many things. I thought I knew a lot about racism, but turns out, I didn't know a whole lot. But I think there's a lot of, like, white people out there who understand their privilege a lot more now and want to help.

Justin Bullock:

I-I think that again, I speak for myself, for Justin, as a black person, there's a mistrust that, I believe that white people care about this right now. And I also believe that there's, like, a news cycle where people... Like, some stuff gets sensationalized. This happened early on with like, kids being killed with like, guns. There's like a sensationalization movement to try and like, change legislation, blah blah. It would like, fade out. It would happen again. And now, it happens, and we don't care. And I guess for me, it- I-I worry that this- it- that this same phenomenon will happen.

And I look at people who talk about, about wanting, like, black leaders in organizations, but then I look at the white leaders of those organizations who are not stepping down. And for me it's like, well, how are you going to get these black leaders? And everyone's like, "oh, oh in time they'll come". I'm currently in the middle of Pedagogy of the Oppressed by Paulo Freire, and he talks a lot about the praxis. Which basically is this combination of critical reflection and critical action. And that critical action without reflection, is just empty activism.

And critical reflection without action is just verbalism, or just like, talking a good game but not really doing anything. And that in order to have true change, you need both. So, I-I don't know if we're always doing both. And I think that is where my- my skepticism, I guess, it comes from.

Diana Cejas:

There is a part of me that is optimistic and is seeing some of these same changes, and really hopeful that this will continue and that we'll actually make some major changes that could improve our healthcare system for the better and improve the kind of care that we end up providing to patients. But I think that one thing that people aren't realizing is that whole reflection piece, and then realizing that regardless of your intent, regardless of if you're a good ally, regardless of whatever personal work you might be doing, just being part of the healthcare system means that you're a part of a system that is harmful particularly to minoritized people that has done a lot of harm, and that continues to do a lot of harm.

Because I think that people think that we're talking about racism, we're talking about ableism, we're talking about discrimination. These are all things that happened in the past. And it's like, no, no, no. No. We have ongoing issues right now. I can talk to any of my cousins and have a story about how they've been mistreated, by physicians or other members of the healthcare system. I can tell my own stories about that. And if we just want to take a look at, like, oh, let's plan for the future, let's make things better, let's do these things right now, and not addressing the harm that has been done, it's really not going to do anything to like, engender trust in the communities that have been hurt and harmed the most.

I'm thinking, it's gonna take a lot of really uncomfortable conversations, and people are going to have to be more comfortable with being uncomfortable. And again, recognizing that yes, okay, maybe you as a person didn't do this horrible thing, but realizing that the system that we're all a part of did, and that it's up to us and on us to make the changes that are going to be required. I think that it's going to take being uncomfortable, it's going to take a lot of investment, and that's investment of time, that's investment as far as resources are concerned. Because one of the things I'm seeing with some of this DEI stuff, and not just, not just at my institution, but kind of everywhere, is that it's like, "we want a DEI committee", or "we want to have these activities". But then you're not giving people the resources to be able to, make plans for certain activities or to get the education that they needed, or you're not giving them the time, and they still have really busy clinical schedules, or you're not giving them the training. There just needs to be a, like, restructuring of the way that we're looking at this. It's not like we're trying to do the DEI stuff on top of everything. It's just something that should be integrated into what we're already kind of doing, but we need to have the time to do that. We need to have the funding to do it as well, and people really don't want to think about that piece. We don't want to think about the fact that if you're wanting people to get educations specifically from people who have been doing work in Diversity Equity Inclusion, or to talk about these things, you've got to pay them.

It shouldn't just be the kind of situation where you're just expecting, like, your one black person on faculty to come and give talks. Pay them. And give them the time to be able to kind of do those things. So, I think that there's going to have to be a whole lot of additional work that we're going to have to do if we really, really want to make these changes, and make it so that it's an ongoing kind of a thing. And then it just can't be at one level. I think a lot of times we're thinking, okay, well maybe if I can just put in a person here that's got this new title of DEI or this new thing that's related to diversity, then that's enough. And it's like, no. Are you looking at every single level? Are you looking at faculty? Are you looking at people who've gotten tenure? Are you looking at the pre-meds? Are you looking before you get to pre-medical school? Is there a pipeline issue that we need to address?

I mean, I would say that there is. Well, let's look and see what that actually is, and then once you get these diverse people into your programs, and into these positions, what are you doing to keep us here? Are you giving us the support that we need? Are you giving us the encouragement? Are you allowing us to thrive? Or is this just a situation where you're like, "all right, I've got you here now", and then you're- we're just kind of left to the wolves and end up leaving? That's not doing anything to help the situation either. So, I think for all of this, there's been a lot of people trying to look at quick fixes, and it took them a long time to get here. It's going to take a lot of work to get out.

Peter Poullos:

What would that take for someone like me to be given a gold star for allyship?

Justin Bullock:

There's this cartoon that if you google allyship, that'll come up, and it basically talks about the fact that allyship is a verb. It's not a noun. It's not a state that you attain. You- you don't get the gold star for being an ally, because being an ally is a continual process. You can be an ally for someone in one moment and then not be an ally for them in a later moment. For me, I'm working to be a better ally to my, like, women colleagues, my non-black colleagues to like, disabled people, like people, like, the black people, like, people like me. It's a constant struggle and challenge I have moments were like, I'm walking down the street and there's somebody who's like hooded and I'm like, "hmm, maybe I should put my phone in my pocket".

And then I'm like, "hmm, that's very interesting", like I wonder like why that like thought process like came through my head. And-and always like, continually, like, pushing my brain to like, question these associations that I have. So, I guess.. there are specific examples. So, for instance, like, there's-there's certainly ways to be allies around micro aggressions. You know? So, for instance, an example of allyship that I didn't do earlier today that I should have, was when Dr. Poullous introduced Dr. Cejas, he called her Diana, and when he introduced me, he said Dr. Bullock. And I didn't s take that moment to correct him. A-and I didn't do it 'cause I didn't want to create this awkward moment and I was like very uncomfortable, it's a podcast, like there's all these things, but like, that was me failing to be an ally. that is allyship. It's a struggle.

Diana Cejas:

I didn't even notice, but thank you, I very much appreciate that. I would say, I would definitely cosign that. I think one of the things that you have to think about when you're thinking about allyship is that it's going to be a struggle. That there's going to be ongoing work that you're going to have to do. I would say, one of the things I usually talk about when I'm talking about advocacy efforts in particular and trying to talk to medical students about how they can use their own platform to advocate for various issues, is to remember that sometimes the best thing you can do is to be quiet and to pass the mic. So, if there is something that's coming up and you're like, "oh, I really want to comment on this, or maybe I don't need to talk about this kind of thing", look and see if there are other people around, particularly those that belong to these marginalized groups who are doing work already, and who maybe have information that you can use to educate yourself.

They're going to be times when I am maybe talking about like a Diversity Equity Inclusion issue that does not relate to me. I don't have that bit of experience, and then what I need to do, if I'm trying to be a good ally, is to look to someone who has that experience so that I can try to see if I can learn from them and grow with them. Sometimes particularly in my field where I work a lot with people of various neuro diverse identities, and people with intellectual disabilities, I don't belong to those particular groups, so I think that one of the things that I can do to help, is be a microphone. I think one of the terms or phrases I hate the most is, like a voice for the voiceless. I can't stand that because everybody has their own voice.

Everybody has something to contribute. And there are things that I can learn from people who have a lived experience so that I can try to be a better ally for them in the future, or as we're kind of moving along. But I think that I can try to be the best ally that I can, but I don't think I will ever be able to label myself a good ally. I think that's the- the people who belong to the group that I'm trying to ally with. I feel like I've said that word 500 times in this sentence, but they're going to be the people who are saying that I'm doing the work or I'm not. All I can do is continually try to educate myself. Check myself when I get something wrong, and if someone calls me out, or calls me in not getting defensive, but really trying to learn the lesson and try to figure out what I can do to make things better the next time.

And then being very vocal in my kind of allyship, I think one of the things that it-it happens quite a few times, but every time there's something like, in the news where it's something horrible has happened or maybe there is another incident where somebody is not very respectful it's always someone coming up to you after the fact to be like, "hey, you know, just wanted to let you know I'm thinking about you. I'm checking on- in on you" and all that kind of stuff, and it's like, okay, that's great, but where were you in the moment? Why didn't you say anything, kind of, in- (laughs) I'm seeing you laughing over there Justin. I did not notice anything but the title thing, but little things like that.

So, someone coming up after the fact, and not really addressing out the- like being a vocal ally when they could have been. I feel like that's not as helpful as it could be. But everybody's going to have moments when you're not quite up to the level where you think that you should be. I think it's not a time for you to be like, beating yourself over the head and being like, "oh, this is terrible", just acknowledge that you maybe could have handled something a little better. Educate yourself, and keep it moving.

Peter Poullos:

It’s funny Justin I do that with residents and fellows. I call them Dr. So and So, or junior faculty.

Justin Bullock:

Hmm. Hmm.

Peter Poullos:

I don't know why. You know what I mean?

Justin Bullock:

Mm-hmm (affirmative)

Peter Poullos:

Like, she's already like, a professor, and we're colleagues, so it's first name, but you're like a resident so I want to elevate you a little bit, although that may not be exactly what I'm doing. That may be just what I think I'm doing. I could be like, doing it to minimize you in some way. I'll have to think about this. But that had nothing to do with sex, it had to do with your different levels of training at the moment.

Justin Bullock:

All I know is, there are studies that show that like, in-in like, grand rounds and stuff... I'm sure you know this, right, that women are more likely to be introduced by their first name and men by doctor such and such.

Peter Poullos:

I can't guarantee you that didn't happen.

Justin Bullock:

Mm-hmm (affirmative)

Peter Poullos:

But I don't think it was for that reason.

Justin Bullock:

Mm-hmm (affirmative)

Peter Poullos:

But thank you for pointing it out.

Justin Bullock:

To riff off of that. One thing I want to shout out. So I have a mentor who is a white woman who is amazing at being an ally, and she's not obsessed with b-being an ally. She just- she does it. She lives it. So Dr. Karen Hauer who's been my research mentor since I, like, started doing any, like, MedEd research. And what she does for me is, she, like, gives me opportunity. She opens doors for me. She connects me with people, you know? When we do- When we were doing, like, like assessment, like studies and I'd say, "oh, like I think stereotype threat could be interesting". She's like, "sure, let's do it". And then- and then adds it in. And like really does, like so many things to-to elevate me as a, like scholar. In a way, a-and not in like a self-righteous way. A-and for me, she is like, been the best ally for me because she is literally like, made my career. You know? And like, has given me so, so many opportunities. And used her place and status of being like, internationally recognized for medical education, and then like, brings me alongside her. And that's allyship.

Diana Cejas:

Yeah, I think that people don't recognize how many doors are closed to black-black physicians, to disabled physicians just because we might not even know that those doors exist. Now I'm thinking about my own, I don't know if I would call him a mentor or a sponsor at this point. I didn't really know the difference between mentorship and sponsorship until I got a sponsor, and it has just been so, like, changing my career for the better, honestly. And I think that that is just someone who's been willing to be like, "you know what? I'm going to use my platform" and this is another person of color, but he was- he's certainly up there in his research and all the work and things that he's doing.

And he was like, "I'm going to open some doors for this person". That person being me and giving me opportunities and experiences that I really did not know were out there. I think another thing that we can think about, when we're working, particularly with trainees, and medical students and things like that who are from multiply marginalized groups, is just to recognize that maybe we were never given certain opportunities. Maybe we didn't know that they were there because maybe people are used to working with people that have a little bit more privilege, or people that are coming from this not necessarily first generation background when it comes to training and things like that. So, one of the things I think I-I totally would agree with, is one of the ways that you could be a good ally is just to be trying to find those-those doors that might be blocked to us and opening them up a little bit.

Peter Poullos:

What is the difference between a sponsor and a mentor?

Diana Cejas:

When I think about the difference, a mentor is like, oh, okay, this might be someone that I sit down with, I'm talking about their career advice, I'm needing specific practical information that comes to doing research projects, like maybe this is a person who can talk to the grant writing and all those kinds of things. Whereas a sponsor might be still doing some of that kind of same stuff, but the thing that I think of that's a little bit different, is that the sponsor is going to be the one who's at a meeting somewhere who says, "hey, this is the- my- this is Diana Cejas, have you met her? She would be great on this paper. Hey, Diana, why don't you come over here, I want you to work with me on this project. Hey, why don't you come over here, why don't-".

If they're the ones who have the grant, they're like, "let me put you on the grant. Let's try to get you some publications. Let's try to see if we can't connect you with some people in certain kinds of fields". So if I'm thinking of my own, I don't even know if-if he knows that I consider him to be my sponsor, but this is a person who very quickly was like, "let's write some papers together", and has put me on a couple of papers with people that are like, way high up the food chain. I'm still a little bitty junior faculty over here, still trying to get my name out there, and he's introducing me to these people that I'm going to be able to make connections with, and who are really going to be able to help me as I continue to try to move up the- the ladder.

So it's... yes, with the mentors I believe you can have those kinds of things, where you have this, like, output with papers or whatever, but the sponsor is gonna be the one who's like, "hey, this person over here", not just in the one to one mentor- the mentor kind of relationship, but they're trying to get you connected with other people too. They're trying to put you out there. They're trying to make sure you have opportunities. They're saying, if there's an advisory board, "you go on it". They're saying, if there's some kind of editorial kind of thing, "you come- come with me and I'll help you write it". They're kind of using their platform to kind of boost you up.

Justin Bullock:

Y-yeah, and the thing that I love about this is, that what happens- what-what we're talking about is, like, these people are not doing things for us. They're just saying, here, like, door open. For me it's like, "Justin, you get to walk through when I walk through. You get to decide whether or not you're going- you know, you do this". Just like, literally creation of opportunity.

Diana Cejas:

Right. Right. So, I mean, people that would have never known me before had no idea who I was, know who I am now because of him. And certainly, again, mentors can do that too, but I think the sponsorship is a little bit of a different kind of a level.

Peter Poullos:

What you're describing seems like, i-it's things that everyone should be experiencing in academic medicine. It almost sounds like, they're treating you like people, and like colleagues. We're supposed to be doing these things for each other.

Justin Bullock:

And yet, it's not happening.

Diana Cejas:

Right.

Justin Bullock:

For so many people like us.

Peter Poullos:

Yeah. That's what really stands out, is the normalcy of what you're describing. Or the normalcy for those of us who asse that this is just normal and happens. I mean, it doesn't always happen for people who are not part of marginalized groups, like you said, the person has to take initiative. Sometimes people fall through the cracks, but what you're describing is how things should be for everyone. I feel like people are starting to try and build these things in, formal mentorship programs and sponsorship programs, and like making sure in your periodic meetings with your division chief that you're getting what you need, but the fact that this seems, like, special or above and beyond, I think is striking.

Diana Cejas:

It absolutely is striking. Now I'm thinking all the way back to when I was applying to get into graduate school, just thinking about the fact that I- there was so much I did not know because I didn't necessarily have the background where like, both of my parents have PhD, or both of my parents are doctors, or both of my parents are doing all this kind of stuff. I didn't know any of that kind of stuff.

Diana Cejas:

So there was a lot of me just kinda figuring out things on my own and trying to figure out how to get there. And even working into academia, like, I have no background. So I was really trying to figure out a lot of different things on my own. And I dare say that that's a really common experience for a lot of first generation, or even if you wanna say second generation students, it's a lot of, - there's a common experience for a lot of people who are Black physicians or belong to multiply marginalized groups.

And I- I think that, on the one hand, it might seem like it's kind of shocking, like, "Wow, we're not getting these opportunities." But then you think about, like, my classmates, or former co-resident- or co-residents whose fathers were program directors, and who have these connections who could be told kind of, "These are the steps that you need to take, this is what you need to do to be able to climb up the ladder."

And just thinking about this is the way that things should be done, yeah. This is the way that things should be done. Yes. There should be this kind of level playing field for everybody. But there's not. So I think that even when it comes down to thinking about how we can address inclusion, diversity, equity, whatever just thinking about trying to level the playing field and how much effort it's gonna take to be able to do that particularly for those of us who belong to multiply marginalized groups, it's gonna take a lot of effort and just acknowledging that the- the field is not level, and some of us are starting at like the goal line and some of us aren't even in the stadium. I think that that's something we can kinda think about.

Justin Bullock:

That is so real. So I went to MIT for undergrad, and I remember my first like calculus test of college. There was one really, really tough problem, and I was like talking about it with someone, and they were like, "Oh, I took multivariable calculus as a sophomore in high school." And I was literally like, "What?" Like, at my high school, if you took any calculus, you were like exceptional, like literally exceptional, land that's like at the beginning of college. and it's interesting, 'cause they actually were wrong, what they told me the answer for that question was, was actually wrong.

But (laughs) regardless , this- this- this playing field, it- I- I completely agree about how uneven it is. , and- and then I think one other thing, particularly thinking about like me with bipolar for someone who doesn't know me, like, I'm a very risky like mentee to take on. , because, like, you don't know when I'm gonna be productive or not productive, you don't know like how my illness goes, and like I think- I think some people probably have some like- like concerns and so- and I think certainly with like different disabilities, this can chan- can be worse. Just to point out that finding a mentor is not always easy.

Peter Poullos:

So that's funny what you said, my dad was a firefighter. I asked him, before I started my internship at UCSF, "Do you have any advice for me?" He said, "Yeah, don't trust anybody." It actually turned out to be really good advice. I didn't follow it. But it wasn't really practical for my career, the first gen thing is also real. Nobody ever told me the rules, not coming from like a privileged background, all I had was the example of the residents and attendings who supervised me in Houston, at University of Texas, and things were a lot different at UC San Francisco and I wish that somebody would've told me the rule book had changed.

Justin Bullock:

I actually feel, - I feel super lucky in terms of like ... like I said, I went to MIT for undergrad. They have like a pre-health ed- like office. They gave you like a step by step, what you should do each year if you're tryna apply to med school when you graduate, like then I got to go to UCSF, I got all these amazing mentors, you know? I stayed there for residency, got- I got to continue with these amazing mentors. You know, I- I feel like I have been very, very, very fortunate, and- and I totally see all the ways in which it has combated so many of the obstacles that I faced. I don't think that most people like me have a similar experience.

Peter Poullos:

Yeah, thanks for saying that. How do we ever get to this point where we're all treated the same and we all have the same opportunities? When you look- when death rates- mortality rates vary by zip code and how much asphalt you have around you, you know?

Justin Bullock:

This Pedagogy of the Oppressed is like my current like hot thing, and Freire, what he says is like in- in most- in the current state in society, what- it's always like there're the oppressors and the oppressed. And in general, in history, it's the oppressed endeavored to become the oppressors.

And so basically, you're never breaking out of the cycle, but you just have a continually oppressed group fighting the oppressors. and instead, the solution is to- is re-humanization, because the process of oppression is one of dehumanization. And so that's like kind of some upper level like type stuff, but I actually think it's hopeful, to me, I guess. 'Cause for me, I fight for like being treated like a human being like with my bipolar disorder, because I think that- like I should be treated like a human being no matter what condition I have. And I fight for like Black residents having fair assessment, because I think everyone should have fair assessment.

And so, yeah, I guess it's like if we focus on re-humanization and maybe we get out of this loop where it's just like only one person can prevail and- and only one person is on top and one person is the dean and one person has all the money and like et cetera, et cetera, et cetera.

Peter Poullos:

See, if you listened to Ronald Reagan and his trickle down economics all of this money that the billionaires are hording right now should've trickled all the way down to the rest of us, and we would all be lifted out of poverty and oppression by now. Is it safe to call that a failed experiment? Probably?

Justin Bullock:

I think so.

Peter Poullos:

Yeah.

Diana Cejas:

Yeah.

Sofia Schlozman:

To Dr. Cejas and Dr. Bullock, thank you so much for taking the time to share your thoughts and experiences with us in this episode. In Part 2, Dr. Poullos continues his conversation with Dr. Bullock and Dr. Cejas to discuss the importance of community and representation for disabled people of color and advice for future healthcare workers listening to this episode.

To our audience, thank you so much for listening or reading along to this episode. We hope you will join us again for Part 2 of the interview.

Sofia Schlozman:

This podcast is a production of the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus Summit program, the Stanford Medicine, Stanford Medical Abilities Coalition, the Stanford Department of Radiology, and the University of Michigan Medical School Department of Family Medicine - MDisability initiative. The opinions on this podcast do not necessarily reflect those of their respective institutions. It is released under creative commons attribution, non-commercial, non-derivative license. This episode was produced by Peter Poullos, Gillian Kumagai, Lisa Meeks, and Sofia Schlozman, with support from our audio editor, Amy Hu.

Transcript Part 2

Peter Poullos:

Doctors with disabilities exist in small but impactful numbers. How do they navigate their journey? What are the challenges? What are the benefits to patients and to their peers? And what can we learn from their experiences? Join us as we explore the stories of doctors, PAs, nurses, OTs, PTs, pharmacists, dentists, and other health professionals with disabilities. We'll also be interviewing the researchers and policymakers that drive medicine forward towards real equity and inclusion. I am Peter Poullos, and I am thrilled to bring you the Docs With Disabilities Podcast.

Sofia Schlozman:

Welcome back to the Docs with Disabilities. This episode is Part 2 of our two episode interview with Dr. Justin Bullock and Dr. Diana Cejas. If you have not yet listened to Part 1, we recommend you do so before listening to this episode. In this episode, we jump back into our interview with Dr. Bullock and Dr. Cejas through a discussion of one of Dr. Cejas’ recent publications. A 2020 Stat news article titled “To Thrive, Black and Latinx Physicians Need Their Communities”.

Peter Poullos:

And, Diana, you, - you wrote an article, and it was published July 9th, 2020. It's called, “To Thrive, Black and Latinx Physicians Need Their Communities”. And you told an anecdote in there, you said at the end of a long, tiring day you're in the emergency department and an elderly patient got your attention. And then I'll just read the quote from here.

Peter Poullos:

"'Excuse me,' he said, 'I don't mean to be nosy, but are you a doctor?' And I looked at him warily and said, 'I am.' And he says, 'May I shake your hand?' He asked as he reached out his hand. He had tears in his eyes as I took it. You don't know what it means to me to see young, Black people doing good things. You don't understand what I had to go through, how we all got beaten, how far we had to go just for you to be able to do what you're doing. Thank you."

Peter Poullos:

And then you said, "After he said that I could've worked all night after that." Can you tell me a little bit about what that- little bit more about that experience and what it meant to you?

Diana Cejas:

Yeah. The first thing that comes to mind is that that's not the only time that's happened, it- it's not just, - and thinking about some of my other- some of my friends, other Black physicians that I know, other physicians of color that I know that have ... it's- it's always seems like it's the- the older, - old men, old women or something like that, it's just kind of take you out of the moment. Like for that particular experience, I was in the ER, I was on consult, it was an incredibly long day. I was tired. I just really wanted to go home, and I couldn't see myself as this person was seeing me.

Diana Cejas:

He saw me, he was seeing someone who was doing some amazing thing that he did not have the opportunity to do. I don't know if he wanted to be a physician when he was young. I don't know anything really else about him other than what he said to me and having a- a very vivid picture of him in my mind.

Diana Cejas:

But just thinking about how- how many times I have had ... and it's not always the older, older people, sometimes it's been younger people, too, who are just like, "Wow you're doing such a good job, I'm so proud of you, I'm so happy to see you." That means so much, especially in those moments. And, I mean, it happens now, but when I was in training, it would mean so much to me. It would just be kind of sustaining for me, because, again, you feel like you're not seen you feel like you're always having to shrink yourself down, you feel like nobody really respects you, you feel like patients don't see you as a physician. Nobody really sees you, kind of, as a physician, they see you as anything but the doctor.

Diana Cejas:

But here was someone who would-, saw me in that moment and was like, "I'm proud of you. I see you. You're doing a good job. I'm so happy to see that you're here." and every time that's happened, it's just kind of been like a little bit of a buoy for me, just to let me know that maybe I am doing something okay. I'm doing something right, I'm- maybe I'm helping my community in some kind of a way. Because y'all can see that I'm here and you can see that I have value and you think that I belong here.

Diana Cejas:

And I think that unfortunately a lot of us don't always feel like we belong in medicine. I feel like a lot of us will question sometimes why it is that we're doing the things that we're doing, even if we love this work. So, I just love it when, - when these people say these things, because, again, it's like you see that I'm here and you see what I'm doing and I- you appreciate me for who I am

Justin Bullock:

I'm reminded of this quote: “the only way to deal with an unfree world is to become so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion.” And I think that's like what all those people are saying to you.

Peter Poullos:

It must mean so much more coming from someone from his background. Like, another Black person who's lived this entire life and have s- has seen all of this discrimination and lived this discrimination, for him to see you, that must even more be the most powerful.

Diana Cejas:

Yeah. I mean, it is, but then I'm thinking about times when I've had moms or caregivers of children will say, "Look, this is your doctor," and I've had like little kids who'd be like, "Oh, my doctor looks like me." That means so much, because my pediatrician was Black when I was very small, but then after that I didn't have any other Black physicians, so the idea that I could beI- I'm not a role model at all. (laughs) The idea that they could see themselves in me it just- it's- it's really- it means a lot.

Justin Bullock:

You are a role model.

Diana Cejas:

I don't know.

Justin Bullock:

To me.

Peter Poullos:

You're both role models to me. You can role model up and down and across, just like you can lead, right?

Peter Poullos:

You know, I've never met either one of you in person, this is, I think, like the second or third time for Justin and third or fourth for Diana, mostly on panels, although Justin and I have met separately, and then of course, you guys were both on the panel in our conference. But I had no idea you were six feet tall and I have no idea if you're vis- if your disability is visible or invisible. It sounds like it's intermittently visible for you, Diana?

Diana Cejas:

Yeah. I’ve kinda gotten to the point I remember right after I got sick, my occupational therapist was gonna be like, "One day, nobody will be able to tell unless they're really looking at you." , so I- I'm- I'm definitely at the point where sometimes neurologists will give me a side eye but most of the time, they just think that I'm holding my hand- like holding my chest, I guess, weirdly, because sometimes I have my hand kind of up a little bit.

Peter Poullos:

That's interesting. You can pass for non-disabled.

Diana Cejas:

I can. And there's a lot of weird feelings I have about that sometimes.

Peter Poullos:

Hmm.

Peter Poullos:

Like, are you disabled enough to be disabled?

Diana Cejas:

Yeah. I definitely had ... especially when I was working through my own identity issues, I had a lot of thoughts about what disabled means, who gets to call themselves disabled, and what exactly that means for me personally, and a lot of hang-ups, I think some of those relating to just general working through internalized ableism about how disabled is disabled enough.

Diana Cejas:

And I think it took for me being in a space and working with other people who were disabled people who are se- self-advocates and things like that before I started to feel comfortable using the term for myself.

Diana Cejas:

And then when it comes down to working with patients as a person with disabilities and how that, I guess, influences the kinda care that I give, especially if I'm working with a patient who is Black and disabled or chronically ill. One thing that I like to think about a lot especially since sometimes I pass and sometimes I don't is like disclosure and how much of myself I wanna share with a patient when I'm in the room. And I actually just wrote something a little bit about when I choose to disclose and when I don't choose to disclose.

Diana Cejas:

Of course, you're gonna feel a little bit more of a kinship with a person who is maybe from a similar background and that can be any kind of background, because I- I also feel the same kind of kinship when I meet somebody who also grew up on a farm, but when we have similar experiences, it kind of makes me want to kind of let them know, "Hey, I've been where you are," or, "I've had experiences like the ones that you've experienced. I want you to know so that you know that I'm here and I'm working for you, with you, and we're gonna work together to try to help you be as healthy as you can be."

Diana Cejas:

I think one thing that I've noticed particularly when I'm working with young, disabled people of color is that there's just so many people that have stories about not being seen or not being heard or not being believed. For me personally, I feel like that is what leads me to disclose to patients more often than not. Like, that, if nothing else, hey, I'm here, and I have a background where I've experienced specific kinds of things with doctors where they don't hear me or see me or believe me.

Diana Cejas:

And particularly, again, for those patients young, disabled people of color, particularly young women of color where I just kinda feel like I want them to know, like, I'm here, I'm on your side, and I know that we don't always get treated right in the healthcare system, but at least you've got me as an advocate and I'm gonna try to see what I can do to help work with you.

Diana Cejas:

And I think that that's just me as a person trying to acknowledge their experiences and as a physician, trying to help mitigate some of the harm that- that our healthcare system has caused people.

Peter Poullos:

I hear this all the time, this not being believed thing, that it's all in your head. And this has got to stop. When are we gonna start believing people? What about you, Justin? Do you have any like similar experience treating Black patients with disabilities?

Justin Bullock:

Yeah. And I- and I wanna first make a comment about the not being believed. For me not being believed, it's a very scary thing because like by definition, one of the features of my disease is like disconnection with reality. So, I have bipolar II. My dad has bipolar I. So, I've never been psychotic.

Justin Bullock:

So, basically, like, it is possible that I that my reality is not the reality that other people experience, and without a person to like really ground against who you really, really, really, really trust, it's very scary and very hard, and like- like terrifyingly like- like ver- ver- for me, very distressing, and that's only happened once, and my reality, I think, at this point has been proven to be, it was the real reality. With mental health, it's a- it's- it's in- it's different. Like if I told my psychiatrist like, if I'm- if I'm like, "I'm sped up." Basically, like, they believe me, in general, about like that type of stuff. So my symptoms, usually people don't- don't question so much.

Justin Bullock:

With respect to patients, most of the patients so I'm- I'm in- in internal medicine who I see are generally older and most of their disabilities relate to like mobility. I mean, definitely a lot of people who have like hearing loss or people who are deaf who don't have any assistive devices that they use, et cetera, so I guess I think I- I think I- I have fewer people who I share like Black patients, who I share like- like Black bipolar patients. Actually, I've never had a Black bipolar patient, I've had many bipolar patients who are not Black, and oftentimes when I see- if I see them, it's after a suicide attempt, if they're in the medical hospital.

Justin Bullock:

I often like find myself a little bit emotionally distant, cause it's a little- it's often like pretty close to home. So that's interesting. I will say there's been one patient in my entire life, d- despite me telling of my peers, all the podcasts. I've had some patients who've, like, known about my bipolar diagnosis from, like, media and then come and talk to me about it positively. But I've only ever disclosed once to a patient. And it was actually after someone who had a pretty serious suicide attempt and was, like, kind of beating himself up for attempting suicide and I basically just sort of said, I mean, kind of shared a little bit about myself. And so, like, to me, it represents that you are struggling. You're allowed to have whatever emotions you want, but I would challenge the, the fact that you're, like, beating yourself up.

Justin Bullock:

And I think one of the sad things about this story, I guess, is this patient recently died. And the reason why I share that is because I had ... probably a week before this happened, months ago, I had a conversation with my therapist, who basically was speaking with his peers when I was not doing well at one point, like, a few years ago. And they basically said like, Justin's probably gonna die. Like, if you look at his, like, like, risk factors and blah, blah, blah, like, he's, like, a very high likelihood of dying.

Justin Bullock:

And so, for that patient to die right after, it really hit me, like, quite deeply. And also the fact that, for whatever reason, I felt compelled to share. And I will say that patient trusted me much more because I shared that with him. And I definitely don't regret it at all. And before I did it, I was, like, asking, like, what's my intention? Am I sharing this for him or for me? Like, d- d- d- all this stuff. But yeah. So, it's kind of a complex, me deciding to disclose is a little bit of a complex decision.

Peter Poullos:

It's a gift that you're giving your patients when you disclose to them. You may not wanna give it to everyone. Sounds like this is sort of, like, political disclosure. Like, Neera Jain talks about it’s analogous to that, right? Disclosure for a purpose. Not just for conversation. Certainly not for your own feeling good.

Peter Poullos:

But, I mean, to utilize it, to build trust or to motivate somebody or to forge a more meaningful doctor-patient relationship. Sometimes a disclosure doesn't need to happen. I also, I had an experience, a personal experience with psychosis last time I was in the hospital, after being totally manic in the ICU and not sleeping, I developed ICU psychosis and started having, like, visual and auditory hallucinations. And I was convinced that the nurses were plotting to get me fired from my job because they were putting together a dossier on what a bad person I was and they had all this proof that I was, like, a horrible person. And I, I could hear them talking about me.

Peter Poullos:

And I was so upset because my wife, like, didn't believe me that I was hearing these things. And, like, the nurses were just, like, blowing me off and they wouldn't even, they wouldn't explain anything to me. They finally put me in a dark room and just refused to talk to me, thinking that, like, I might sleep and that would make me better. But I just thought that they were, like, punishing me and getting ready to fire me. It was terrifying. It was the most terrifying experience of my life to feel like everyone around me was, like, lying to me and plotting against me. It, that, like, disconnect from reality is, I think, one of the scariest things somebody can experience.

Justin Bullock:

Yeah. Yeah.

Peter Poullos:

Is there anything else that you would like to say? Anything that you wished that I would have asked but didn't?

Justin Bullock:

If I could give advice, it would be, I don't believe that I am special in any way. I believe that I just had opportunity and I think that this is advice to Black people and not Black people, actually. There's a quote, I love quotes, like, luck is when hard work meets opportunity.

Justin Bullock:

And really, like, push people to actively seek out someone to mentor them. Help give them guidance. Also recognize that people sometimes don't have the capacity to take on someone for a full-time mentee but can have a one-time conversation, or can give you recommendations for other people to talk to, and I think also, specifically to the Black, disabled overlap just because you don't see someone who exists with your overlap does not mean that they don't exist, and oftentimes, we are just trying to survive and (laughs), like, don't have the capacity to, to be visible, and so and, even if, and if we don't exist, then, like, you can be that person to exist and to make space

Justin Bullock:

And the last thing is visibility is a choice. You do not have to be visible. It is not your duty. You do not owe anyone, like, that, if it is something that moves you, then I definitely encourage you to do it and to be thoughtful about it and to protect yourself. But it is not your job to be the face of X, Black, disabled, overlapped, or any two circles, four circles.

Diana Cejas:

I would strongly co-sign that last part. Like, it's not your job. You don't have to be anybody but who it is that you are, when I've been talking to medical students and also some pre-med students lately most of them ... although I have, well, I have had a few Black, disabled, medical, something, trainees who have I've been talking to lately who are just, really just trying to figure out where they what they need to be able to do to get in. And I'm just kind of, like you fit wherever it is that you belong.

Diana Cejas:

I guess what I was trying to say is that I would not have known that this would be what my career would look like. And I'm just getting started. Like, I feel like I graduated, like, last week, but I'm here trying to do a little bit of work. I certainly wouldn't have thought that this would be the trajectory of things for me, especially when I was back in medical school, trying to envision what my career would look like in the future.

Diana Cejas:

I think that there are so many prospective medical students and prospective residents who have just been told no. Like, this is not gonna happen. You can't do this. Nobody's out there doing that. And I would just say, just take all of those no’s and be like, all right. Bet. I got you. And just go ahead and do whatever it was that you were planning on doing in the first place. It might not end, even end up being what you think that you're gonna be. Like I thought I was going to go into general pediatrics. I mean, I'm still a pediatrician, but I'm within neurology.

Diana Cejas:

But you keep an open mind. Figure out what it is that you wanna do and then don't let anybody tell you no you can't. I would say go and try to find out who is gonna fight for you and find, find that, find that person early, whether that means, like, a mentor someone that has maybe some of those overlaps like Justin was talking about. Maybe someone who doesn't exactly have the exact same kinds of picture, but someone who has been in the game for a little while who can give you some advice. It could be a mentor. It could be a sponsor. Or who can just like to fight for you.

Diana Cejas:

I think one of the best things about my other mentors is that I firmly believe that if we were ever in a back alley fight, that she would knock somebody out for me. You need that in your life. So, I would try to see if I couldn't find someone who could just try to kind of guide you and help you grow. I would say again if you are disabled and if you are a trainee or you're disabled and you're thinking of getting into healthcare and you don't know if you can do it talk to those of us who are openly talking about our disabilities. And I think that you'll find that even people that aren't open about it, like, that doesn't mean that they're not there. One of the most pleasant surprises that I had when I was in training and started to be a lot more vocal about my experience was that I started meeting so many other people who were disabled and chronically ill who just weren't loud about it, and just cause we're not loud about it doesn't mean that we're not out here.

Diana Cejas:

But certainly do what you need to do to be able to get to where you need to go and to be able to get to where you need to go safely. And just, again, underlining that you don't owe anybody anything. You don't owe anybody explanations. You don't have to dump, like, trauma dump in your application essays. Just try to figure out what you need to, what you need to do to get to where you're trying to go as far as your career is concerned. But be able to do so in a way that you're gonna be safe and a way that you're gonna be able to be healthy from a mental and physical perspective.

Peter Poullos:

Trauma dump. That's a new term for me.

Diana Cejas:

Yeah. I heard that from, I think it was one of the med students I was working with was talking about their r- residency application and how they feel like they're compelled to talk about the worst thing that's ever happened to them. And I'm like, you don't have to share that story if you don't want to. If you want to, that's fine. But you don't really have to give out all the salacious bits if you don't want to. That can just be for you.

Sofia Schlozman:

To Dr. Cejas and Dr. Bullock, thank you so much for sharing your time, your insights, and your advice with us today. It is always an honor to hear both of you speak, and I think that this two-part interview will be an excellent resource for those with BIPOC and disabled identities planning to enter healthcare fields, and those without these identities who are seeking to better support their classmates, their colleagues, and their peers.

To our audience, thank you so much for joining us for this episode. We hope you will subscribe to our podcast and tune in next time.

Sofia Schlozman:

This podcast is a production of the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus Summit program, the Stanford Medicine, Stanford Medical Abilities Coalition, the Stanford Department of Radiology, and the University of Michigan Medical School Department of Family Medicine - MDisability initiative. The opinions on this podcast do not necessarily reflect those of their respective institutions. It is released under creative commons attribution, non-commercial, non-derivative license. This episode was produced by Peter Poullos, Gillian Kumagai, Lisa Meeks, and Sofia Schlozman, with support from our audio editor, Amy Hu.