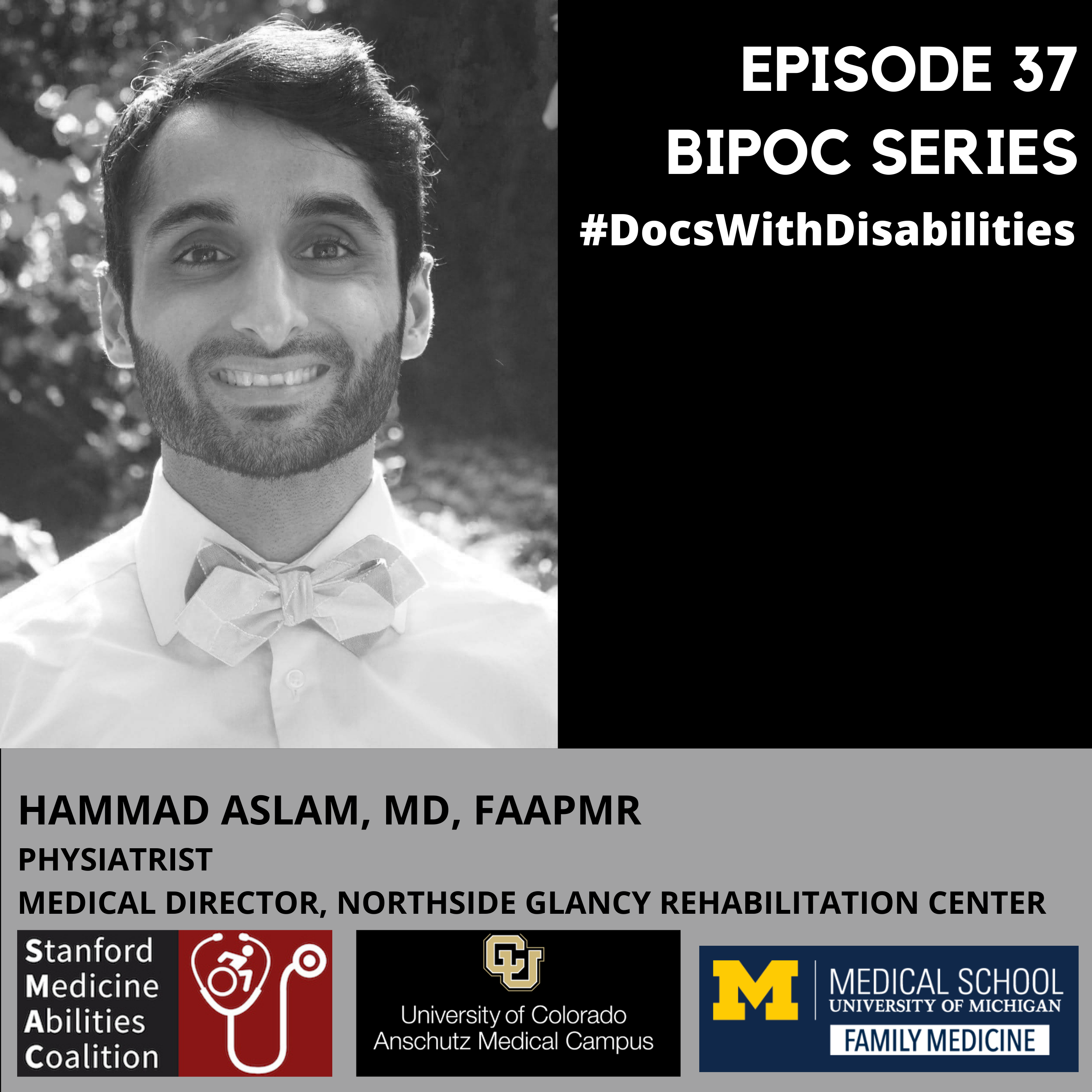

As a young adult, Dr. Hammad Aslam was in an automobile accident that caused a traumatic brain injury and a T2 complete spinal cord injury. In this episode, he discusses his journey through medical school and residency, the impact of mentorship throughout his career, how being a wheelchair user has shaped his relationships with patients, and his outlook on life. Dr. Aslam shares how disability has leveled the playing field and allows him to connect with others despite differences in race, religion, and cultural background.

Guests:

Podcast Co-host, Peter Poullos, MD, Clinical Associate Professor of Radiology, Stanford Medicine and Founder and Co-Chair, Stanford Medicine Abilities Coalitiion (SMAC)

Hammad Aslam, MD, FAAMPR, Physiatrist, Medical Director, Northside Glancy Rehabilitation Center

Transcript

Peter Poullos:

Doctors with disabilities exist in small but impactful numbers. How do they navigate their journey? What are the challenges? What are the benefits to patients and to their peers? And what can we learn from their experiences? Join us as we explore the stories of doctors, PAs, nurses, OTs, PTs, pharmacists, dentists, and other health professionals with disabilities. We'll also be interviewing the researchers and policymakers that drive medicine forward towards real equity and inclusion. I am Peter Poullos and I am thrilled to bring you the Docs With Disabilities Podcast.

Sofia Schlozman: (Narration)

Hello, and welcome back to the Docs With Disabilities Podcast. In this episode, we are joined by Dr. Hammad Aslam. Dr. Aslam is a physiatrist in Duluth, Georgia, as well as a speaker, writer, and disability advocate. Dr. Aslam experienced an automobile accident as a young adult that caused a traumatic brain injury and a T2 complete spinal cord injury. In this episode, he discusses his journey through medical school and residency, the impact of mentorship throughout his career, and how being a wheelchair user has shaped his relationships with patients, and his outlook on life.

Peter Poullos:

Good morning, Dr. Aslam, welcome to the Docs With Disabilities Podcast. We're so excited to have you on for this episode.

Hammad Aslam:

My name is Hammad Aslam. I'm a physiatrist in the Atlanta area. I did my medical school at the Medical College of Georgia and then residency at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and then a fellowship in spinal cord injury medicine at Stanford.

Peter Poullos:

I'd just like you to tell the audience a little bit about what your life was like before your spinal cord injury.

Hammad Aslam:

I was always participating in physical activity, in sports, swimming, climbing. I loved weightlifting, going for hikes. I liked going for walks. I loved just going around traveling, seeing new things. And then all that suddenly changed when I was involved in the accident. And then I realized I had to discover new things to do and build a new life for myself.

Peter Poullos:

You had not only a complete spinal cord injury, but also a severe brain injury.

Hammad Aslam:

Yeah, that brain injury, I feel like that was the part where I felt like I denied it more in the beginning. I felt like I could do everything the same. When... before my injury, things just came extremely easy to me, and I was very confident in myself. Then all of a sudden, after the injury, when I had to start medical school, just a year after my injury, I wasn't as confident in my abilities. I was still trying to get accustomed to my new life, to my new body, and the way my new mind worked. It was a lot to accept all at once. And I had to make certain learning adaptations, I had to learn in different ways.

Peter Poullos:

What exactly was that like studying with a brain injury?

Hammad Aslam:

I would read things and I felt like it didn't stick. And so I would just keep trying to read it instead of trying to go about things in a new way. I kept trying to hammer thing the way I thought that it should immediately just go into my head, but it wasn't working like that. So I had to relearn. I discovered different ways of studying, for example, lectures that I'd found online, videos. And then I had some really great mentors in residency who guided me and I got through medical school, I passed all my board exams on the first try. I did well, I got into a great residency program somehow (laughs). And they said, "You know, your, your knowledge is there.” It's more about, I think the lack of confidence that I had.

Once I got over that, well, you know, some of my attendings really trusted me with my medical management, trusted me with responsibilities and that empowered me. And that helped me to overcome a lot of things that I had probably mentally blocking me and preventing my own progress with things.

Peter Poullos:

You talk about a turning point in your video where one of your attendings gave you more autonomy than anybody else had given you, left you alone with the patients, and let you run the service. Who was that? And what did that feel like?

Hammad Aslam:

That was Dr. Law in Alabama. He was an amazing attending and just an amazing person. You know, he was actually a pediatric physiatrist. So maybe that's why, because he saw a lot of children who were born with physical disabilities, such as cerebral palsy, or who may have acquired disabilities such as spinal cord injuries or brain injuries when they're very young.

So maybe that's why he was so attuned, and he didn't treat me any different than anyone else, except for the fact that he trusted me, he really trusted me. He knew that I could take care of the patients, just like any other physician could. And so he would say, "All right, you know, service is yours, I'm going to go see some other patients in the clinic. And, you know, you can deal with whatever issues come up." And I said "Okay."

Peter Poullos:

What was it like for you in medical school using a wheelchair? What was it like with your classmates? How did it affect your friendships and how did it affect your treatment by faculty members?

Hammad Aslam:

So my faculty members and peers in my class were all amazing. They all helped me out and not in a derogatory or offensive way either. Sometimes you hear about people going out of the way and making someone with a disability feel like they're a child. I feel like my peers were very much well-tuned to that. And they kept me on their same level as did the faculty members there.

Some of them knew that I needed the help with certain things such as the physical exam. And so I had faculty members staying after class or coming in at different times to show me how to do things and how to adapt to certain physical exam maneuvers while in a wheelchair or while using a standing wheelchair, which I acquired.

Hammad Aslam:

My peers, oh man, certain classmates I have, you know, I'll never forget them just for the things that they did, whether that was providing emotional support and letting me know that I could do things, but also physical. I remember one student who I'm actually working in the same hospital with him now, he basically went through all the things in the anatomy lab that I couldn't see properly because I'm in a wheelchair, even with a standing wheelchair, it's difficult to see certain things in the lab, things in the, the human body. So he actually patiently went through so many things and I'll always be grateful to him for that.

Peter Poullos:

I had a very similar experience in my residency in radiology at Stanford. I couldn't even deal with some of my personal care in the beginning. And people like my residency coordinator actually went out of their way to help me with that stuff even when we couldn't get assistance through the hospital.

And actually, my classmates too actually, provided some personal care for me, that would have been difficult or very expensive to have all day long. So yeah, it's pretty amazing. You know, the side of humanity that you see after a spinal cord injury gives you a window into the kindness of others, don't you think?

Hammad Aslam

Oh, absolutely.

Peter Poullos:

Sometimes I think about what if I could go back in time and not have the spinal cord injury?

Hammad Aslam:

Yeah-

Peter Poullos:

Of course, like that would be great, I would have loved to not have a spinal cord injury.

Hammad Aslam:

(laughs)

Peter Poullos:

But at the same time-

Hammad Aslam:

Yeah.

Peter Poullos:

... like, it would also be hard for me to let go of what I've seen and what I've learned along the way.

Hammad Aslam:

Absolutely.

Peter Poullos:

I wish I could switch back and forth between timelines.

Hammad Aslam:

(laughs) Yeah. Yeah, me too.

Peter Poullos:

I could come here and be a radiologist and hang out with my spinal cord injury-

Hammad Aslam:

(laughs)

Peter Poullos:

... and then I could go for the weekend and take a jog and a bike ride in my other life.

Hammad Aslam:

I mean, even just the, the way I'm able to interact with patients now, it's so much more beneficial that I feel like I can't do the same thing if I was able-bodied. I feel like I wouldn't be able to connect with the patients the way I am able to do so now.

Peter Poullos:

Yeah. Tell me about that. Part of our argument for more doctors with disabilities in medicine is exactly what you're saying that because you've been on both sides of the curtain, so to speak, you understand what it's like to be a patient and you're able to provide more, I would say, culturally humble care or more empathic care. Tell me what makes you a better doctor now than you would have been able-bodied.

Hammad Aslam:

I feel like having a disability automatically connects myself to people in a way that other identities cannot. For example, I've had many patients who I am very different from. If you look at me, I'm brown, I'm from South Asia, my name is Hammad Aslam. I'm clearly foreign. And, you know, I practice down here in the South. Some of my patients, you know, don't have many interactions with physicians who, who are from another country or anyone from another country or another religious background.

My background I'm from Pakistan. And the thing is like just having an injury connects me with them, no matter how different we are in terms of race, religion, cultural background, anything like that. I'm able to connect with them and bond with them because we both have suffered in a way. We both have seen the fleeting nature of life and how things change, because we've both seen that in our own unique way, we're able to connect with each other.

I'm able to form that bond with them. And some of my peers have told me this, that the patient may trust me more than they'll trust someone else. They sort of trust someone who's able-bodied like an able-bodied physician, just because I've, you know, "been there and can feel their pain."

Peter Poullos:

What sort of accommodations did you ask for or get in medical school?

Hammad Aslam:

In medical school, I had a standing wheelchair that someone very, very generously purchased for me. And in addition to that, there wasn't a whole lot of accommodations. I think that was more because of my stubbornness more than anything, you know, me saying, "No, things aren't different. I can do everything the same."

I feel like I could have had more accommodations if I asked for them, but nothing that really held me back. When I was diagnosed with ADHD in medical school, after my brain injury, they allowed me to take the exam in a separate room and have just time and a half. And that just helped me out right there.

Peter Poullos:

Yeah, that's really important for people with learning disabilities or any sort of cognitive issues. So that's good. I was actually going to ask you about that, the accommodations for the brain injury. But how did you examine patients from your wheelchair?

Hammad Aslam:

So my standing wheelchair, it allows me to stand up and has a chest strap that holds me in because I don't have trunk stability. So with that, I'm able to do, in addition to reaching them and, you know, just checking their heart and lungs in bed.

In residency, you know, my specialty is physical medicine and rehabilitation, on my sports medicine rotation I had to do a lot of shoulder exams and knee exams and shoulder injections and knee injections. And so being able to stand up, reach forward, which I obviously cannot do. I can't even reach forward without accommodations. Being able to do those things, it was a game-changer. And I was able to do a lot of injections, patient examinations.

It's not something I wanted to do every day because the standing wheelchair is extremely heavy. And as I said, it's an accommodation, it's bulky. The most frequent injection I do is just like a trigger point injections in, like, their neck or upper back. And those I can just do from my normal wheelchair.

And patients I found are when they see me, they're more than willing to accommodate me. They're... Like, even though they just may have had an injury, they're like, "Oh, le- let me get closer to you. Let me scoot forward." And I'm like, "You just fractured your hip. You don't need to, you know, accommodate me." (laughs)

Peter Poullos:

Are there any things in the physical exam that you can't do or you just skip?

Hammad Aslam:

I remember in medical school, especially when we have to do like a head-to-toe, full physical exam for our OSCEs and for, like, the Step 2 CK, just learning. If I can't quickly maneuver from one side to the other, just doing everything on one side of the patient's body or it was one region and then moving and doing the other region. That's something that they taught me how to do in medical school.

Other than that, there isn't a whole lot I couldn't do. I mean, we know that having someone bend over and test them for scoliosis is a little bit challenging or testing even like their feet for clonus while they're just sitting down is a little bit difficult. When they're lying in bed, I can typically examine patients a lot easier.

And I found that for individuals who may be hesitant about pursuing medicine, everywhere I've been to, people... as I've said before, are more than willing to make accommodations, they'll make accommodation before I even ask. You know, before I even came here to this hospital, they were still using paper charts. And so they moved all the charts lower, put them on different area, just so I could reach them when I came here. If they found out the doors were a little bit heavy, they automatically installed the automatic doors places.

Peter Poullos:

Without your even having to ask?

Hammad Aslam:

Yeah. Without me even having to ask. (laughs)

Peter Poullos:

That's pretty awesome.

Hammad Aslam:

Yeah. Yeah.

Peter Poullos:

Did your call schedule ever need to be modified so you didn't have to take overnight call, or did you just do the same as everyone else?

Hammad Aslam:

No, no, it was modified. I remember on my surgery rotation I didn't have to take overnight call. For my OB-GYN rotation, it was in-house so I had to stay there overnight. It was like three days a week. It was just 24-hour call, but I had a nice room to stay in the hospital, accessible bathroom. So that was, that was fun.

In residency, I had in-house call where I stayed there. It was a completely accessible room with an accessible shower. They even put a shower bench in there for me, you know, if I needed a shower. So that was great. They made a lot of accommodations for that through residency.

Peter Poullos:

What did you do on your surgical rotation? Did you still scrub into surgeries?

Hammad Aslam:

I did. Yeah, I scrubbed into surgeries. I delivered babies, C-sections. A standing wheelchair was key. Scrubbing into surgeries was different. I had to stand up in front of the sink and you get fully scrubbed in. Then, at that point, I'm sterile. Someone else had to pull me down, position me in front of the patient on the operating room. And then stand me back up.

Peter Poullos:

Who did that for you?

Hammad Aslam

Usually one of the scrub techs would help me out.

Peter Poullos:

Wow. That's awesome.

Hammad Aslam:

Yeah. (laughs)

Peter Poullos:

Yeah, I wondered about that, but the wheelchair isn't sterile, but that's fine, right? Because it's partially covered by your gown.

Hammad Aslam:

It's partially covered by the gown. The only thing that was, I guess, overlooking the patient was me in, you know, fully covered gown. I know because I was standing up. So everything that was waist up was just covering the gown. Below my waist, there would be like the tires and everything, but that would be out of the field less basically like shoes, scrub shoes, and that actually would be behind.

Peter Poullos:

Did you use that chest strap when you were in the standing wheelchair?

Hammad Aslam:

Oh, absolutely. Yeah. Yeah.

Peter Poullos:

Did you get to retract?

Hammad Aslam:

Oh, yeah. I had to hold retractors for a while, but on my OB-GYN rotation, I remember my attending, she would let me, like, close up and do a lot of things. So that was great.

Peter Poullos:

Wow, that's awesome. Well, I think that a lot of pre-med and medical students are going to be encouraged by this conversation.

Hammad Aslam:

Oh great. (laughs)

Peter Poullos:

There's going to be people in the audience who are listening to this and are going to say, "Oh, well, that's nice for you." You guys have visible disabilities, you're in a wheelchair, that engenders, you know, sympathy and understanding. But for those with invisible disabilities and chronic illness, I think that their experience is a lot different. I was going to ask you about the difference between visible and invisible disabilities and the treatment that one might receive.

Hammad Aslam:

I think that's very unfair the way there's a distinction between visible and invisible disabilities. My brain injury was technically an invisible injury. For me, that was more of a hindrance and more of a barrier to success for me throughout medical school and residency than my wheelchair ever was. Even though people saw my wheelchair, for me, the brain injury, the lack of focus, the anxiety that came with that was huge. I mean, it, it affected everything from school to my relationships, my, you know, my married life.

It takes a lot of courage to be outspoken on the invisible disabilities. I feel like it takes a lot more courage for all the people who have intellectual disabilities or psychological disabilities, diseases or disorders that affect them. Being outspoken about those things takes a lot more courage than me who just rolls in in a wheelchair and people will say, "Oh, okay, we’ve got to make these accommodations for him. We’ve got to help him out in that way."

Peter Poullos:

Yeah. I mean, there's a lot more issues around disclosure because with us, there's no way to avoid, (laughs) you know, disclose-

Hammad Aslam:

Yeah. (laughs)

Peter Poullos:

... soon as I walk in with my crutches or my segway or you with your wheelchair, people sort of understand immediately-

Hammad Aslam:

Absolutely.

Peter Poullos:

... and they get it-

Hammad Aslam:

Yeah.

Peter Poullos:

... and we don't have any option about disclosure, but for some people, it's a very difficult decision whether or not to disclose. And there's a lot of fear that they have that disclosing will

Hammad Aslam:

Yeah.

Peter Poullos:

... have a negative impact on their career. For people with less visible disabilities, they’re often met with skepticism or there are accommodations are denied.

Hammad Aslam

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Peter Poullos:

Especially mental illness is severely stigmatized still in medicine. So lately, I've been trying to be more open about my struggles...with mental illness and depression and anxiety just to try and normalize that. I mean, I don't know how you can be a doctor and not be on Prozac.

Hammad Aslam:

(laughs) Yeah, I agree.

Peter Poullos:

You do talk about in your TEDx talk from 2018 that you did suffer some discrimination or mistreatment or were treated differently by people along the way. Can you tell me a little bit about that?

Hammad Aslam:

Absolutely. Ah, it's an ongoing thing. You know, I've, I've been talked down to, people have patted me on my head before, I've had people talk to my wife and not to me. They talked about me to her as if I wasn't even there.

Peter Poullos:

Oh, my wife gets so mad when they do that.

Hammad Aslam:

(laughs)

Peter Poullos:

Oh, she gets fired up. She's like, "Why are you talking to me? Talk to him."

Hammad Aslam:

Exactly. Exactly. It's so frustrating. (laughs) I, I think it's changing. I mean there's more representation of individuals with disabilities in the media. And I think that people are seeing that and things are changing, but still, it's hard to overcome. There isn't as much representation in the medical field as we've talked about. People still have the perception that an individual who has had a severe injury or was born with a physical disability or a mental disability, they cannot do the same things that other people can do. I feel like that barrier will continue. And it's just a struggle that we'll have to keep working against, yeah.

Peter Poullos:

Has anybody ever asked you if they can pray on you or lay hands on you to heal you?

Hammad Aslam:

Yes. Oh, man. I just finished a book by Zach Anner and he was talking about the three people you meet at a bar when you have a disability and that's one of them. You know, there's always like the high five person who's like, "Oh, yeah." You know, "glad you're out here." But there's always that person who wants to pray on you and I've had many, many people pray on me, pray for me. And I guess they're confused why I haven't been healed instantly, but it happens all the time.

Peter Poullos:

Sometimes I actually pretend to be healed.

Hammad Aslam:

(laughs)

Peter Poullos:

I have done that before. They'll ask you afterwards, like, "Are you better?"

Hammad Aslam:

Oh, yeah. (laughs)

Peter Poullos:

What does the word inspirational mean to you?

Hammad Aslam:

Oh, man. Inspirational, unfortunately, it's lost its meaning now. It seems like a meaningless term that's thrown around by people who just see something interesting. And a lot of times the word inspiration or inspirational is used by people who and they... what they mean by is, "Well, I'm glad it's that person and not me." You know. (laughs) They say, "Oh, that person is so inspirational." What they're saying is, "Oh, I'm glad that person has a disability and they're doing what they're doing, but I'm glad I don't have to deal with that."

Peter Poullos:

Yeah, I agree. And people have such low expectations of those with disabilities that just doing ordinary things like getting up in the morning and going to work makes you inspirational.

Hammad Aslam:

And many people in the gym tell me like, "Oh man, you're my inspiration." I'm like, "I'm just in the gym doing, (laughs) you know, some minimal physical activities just so my shoulders don't go really bad in a couple of years. I don't know how that's inspirational.

Peter Poullos:

In your YouTube video you talk about the importance of language and how language shapes the way that people view those with disabilities. Tell me more about that.

Hammad Aslam:

Absolutely. The words that we use can really define and either box in a person or free them and allow them to discover more things and really reach their potential. If we are constantly telling someone with a disability or not telling even, just treating them as if they can only do certain things, if they can only, you know, pursue certain specialties. Those are in medical school now, but they can only pursue certain specialties because they have a disability or the fact that they are disabled. Even that word implies that that person as an individual is not a whole, that there's something wrong with them, that they are not complete. And therefore, not able to do certain things, not able to be certain things, or feel certain things.

Peter Poullos:

What sort of language do you use about yourself? Do you consider yourself to be disabled?

Hammad Aslam:

I do not. I say that I have a disability or that I am a wheelchair user and that's more of a broad term. If I'm trying to find out that, for example, the accessibility of someplace, I say I'm a wheelchair user. And that way they can just say, "Oh, okay. He just uses a wheelchair. That person is not disabled. That person is not defined by it, but he's just a wheelchair user."

And so, that change in the way we use that word or changing the way we refer to someone really prevents the closing in of a person and what they can or cannot do or how we perceive them. A wheelchair user is definitely different than someone who's disabled and can't do anything. Just those two perceptions.

Peter Poullos:

Why did you decide to become a physiatrist?

Hammad Aslam:

I decided to become a physiatrist because it seemed just like the perfect fit for me. I mean, our philosophy of physiatry is increasing a patient's function and quality of life. For me, that's what I was trying do for myself. That's what I've been trying do for myself for many years.

I was first exposed to physiatry as a patient after my injury. And I discovered that this was the best way that I could connect with patients, I felt like. It just absolutely fit my personality in that I would have a lot of patient interaction. I would be able to speak to patients, discover what is... was holding them back from doing the things they want to do, whether that was pain, spasticity, bowel or bladder issues, I can help them with all those things.

Peter Poullos:

What was your experience at Stanford like for your spinal cord injury fellowship?

Hammad Aslam:

Oh, my experience there was great. I had a lot of interaction with patients who not only had spinal cord injuries, very, uh, recently. I also spent a lot of time at the VA in Palo Alto where patients had spinal cord injuries for decades, 30, 40, 50, 60 years. And just seeing how they were, that was eye-opening for me.

And my attending physicians were all awesome. They all treated me and taught me very well. Dr. Ota is actually, he's the director of the spinal cord unit at the Palo Alto VA. He's actually a wheelchair user himself. His injury level is even higher than mine, he has a cervical level injury and seeing how he's a total rock star, that was super cool.

Peter Poullos:

Yeah. Dr. Ota is great. He actually visited me in the hospital. I was in at Santa Clara Valley as a patient. He actually came to visit me when I was still very paralyzed and just gave me encouragement that I could return back to medicine and practice. And he told me about his experience getting injured in medical school and I thought that was really generous of him to come. And I even thought for a second about doing that spinal cord injury fellowship. I had the opposite reaction as you did.

Hammad Aslam:

Really?

Peter Poullos:

I wanted to separate my spinal cord injury from my work... But I, I think what you did is smart in that you bundled it all together and it makes sense. So, are you in a private practice now?

Hammad Aslam:

I'm part of a private practice, but I'm mostly over here in Gwinnett County. I'm the Medical Director of Northside Glancy Rehabilitation Center in Duluth, Georgia, which is like 20 minutes from where I grew up, 20-minute drive so it's good to be back home.

And I love what I do. I love my patients, every single one of them. And I've had actually friends' parents as my patients here or I've had one of my faculty members from school. I've had her as my patient here. I feel like I'm giving back to community, the community where I grew up.

Peter Poullos:

In this blog post, you wrote entitled Life After you said the following, "I will never be able to ride a rollercoaster again or know what it's like to hold my wife's hand while we stand barefoot in the sand on a beach. But there are other things. Each day is a beautiful day, things are not taken for granted, anger and other negative feelings are not an issue. Quality, not quantity. This accident, eight years ago, is the best thing that could have happened to me."

Can you elaborate on that?

Hammad Aslam:

Absolutely. I remember that's actually one of the things my wife told me that drew her to me was the fact that I didn't take things for granted and that everything was so wondrous and new to me. Every single morning I wake up with a smile, just glad to be here. And it's the way I come to work. I treat my patients and whenever people ask me how I'm doing, I always say, you know, "Awesome, I'm doing wonderful." Because it's true. And being caught up in the past, thinking about what used to be and what I can't do now, that's just a slippery slope and that's not a great way to live life for anyone, whether your life has changed dramatically or if it hasn't. We can always compare the way things are now to the way things used to be or the way things could be.

I still meditate and I still do all basically mindfulness techniques. And that keeps me focused on this moment and not worrying about what used to be and what could have been. Each moment that we have is so, so beautiful.

Peter Poullos:

That's good that you use those mindfulness techniques and meditation. I use wine,

Hammad Aslam:

(laughs) great technique.

Peter Poullos:

... wine, denial and-

Hammad Aslam:

(laughs)

Peter Poullos:

... wine, denial, repression and-... and humor, I guess. But I should try, I should try your techniques.

Hammad Aslam:

(laughs)

Peter Poullos:

Although, you know, I do hate it when people say, "Oh, you're so positive."

Hammad Aslam:

Yeah. Yeah.

Peter Poullos:

As if they expect you to be just bitter, and angry, and miserable.

You write about your wife, and you say, "What is astonishing is how Zainab sacrificed so many things in her life and willingly decided to be by my side, despite all the changes in her life that she has made and would have to continue to make." Now that is commendable. That is what makes a hero.

Hammad Aslam

I stand by that statement. That is what makes a hero. I was put into this, I never asked for it. I was put into it, I'm dealing with it. But she saw what I'm dealing with. She knew that her life would be different. She willingly went forward and agreed to marry me. (laughs) She said yes. She continues to live her life, even though it's completely different.

She’s a mom, you know, Mother’s Day is coming up on Sunday. We have a two-year-old at home. Her life is completely different than all her best friends who are also moms. In that, unfortunately, she does have to take the brunt of the work, bathing him, putting him to sleep just because I cannot physically do those things. So that's an inspiration. I'll use the word there. (laughs) Yeah.

Peter Poullos:

You know, yeah, I'm in the same situation. We actually have a nine-month-old at home.

Hammad Aslam:

Wow.

Peter Poullos:

And yeah, I mean, when I read this quote in that same article and it very much hit home, I'm just going to read it because it's something that resonated with me as a disabled parent. And you say, "When we go out, she does not only have to think about and manage herself, but also our son Laith and me. It’s not uncommon for her to be on busy streets unloading Laith, Laith's stroller and bag, and then my wheelchair while making sure we're all safe. Flying is a whole ordeal in itself." And then you go on to say, "Laith is almost 17 months old and I'm still physically unable to pick him up out of his crib or lie him down. I cannot put him in his highchair to feed him. I cannot put him in and take him out of the bathtub to bathe him. I've seen her get by with little to no sleep for months while she took care of Laith on her own. She does all these things and so, so much more."

Hammad Aslam:

Yeah, yeah. That first year, especially, what you're going through is an extremely tough time, especially when they're so small and squirmy. Now he's two years old, he's tall, he can walk on his own. So it's a little bit easier for him to... He enjoys hopping on my lap and going for a ride around the house. You know, he jumps from my lap to his highchair now. He's able to boost himself up in his crib and then just kind of hops onto my lap when he wants to come out. So he's become more independent, which has made it easier for me.

Peter Poullos:

What do you think we can do to increase representation of doctors with disabilities in medicine?

Hammad Aslam:

I think that will take strategies, you know, on many different levels from the individual level, changing our perceptions on individuals with disabilities, all the way to the legislative and community level, making everything accessible and making things more inclusive in terms of not just sidewalks and facilities, but making schools more inclusive.

It starts from the elementary school and middle school, high school, and seeing representation and seeing other individuals with disabilities in these environments will allow those individuals to flourish. And eventually, if they want to become doctors can become doctors or pursue their other goals and specialties, or some individuals who may then see those individual disabilities and they themselves become someone with a disability themselves, they can see like, "Oh yeah, I remember you know, when when I was in college in undergrad, there was someone in my biochemistry class who was also in a wheelchair and she wanted to be a doctor. So I can be one too."

Peter Poullos:

Yeah. I mean, that's part of what we're trying to do with this podcast.

Hammad Aslam:

Yeah.

Peter Poullos:

Right? Lisa calls it asynchronous mentorship.

Hammad Aslam:

(laughs) That's true, yeah. Right.

Peter Poullos:

And talking about these issues and showcasing physicians and other professionals who are successful in their careers that we can encourage other people that they can do it also.

Hammad Aslam:

When I was in residency at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, there was the Lakeshore Foundation there, which was the Olympic and Paralympic training site. And that was where I interacted with other individuals with disabilities for the first time, because, you know, I had my injury and then started medical school, didn't really have much interaction with other individuals with disabilities until I went to the Lakeshore Foundation. And saw it was used as a way to level the playing field and show that, "Hey, life's not over. Hey, you know, we're still playing sports, doing great things." And they encouraged physical activity and health there. And that's something that was important to me before my injury. And it still remains important to this day. I feel like sports and just getting out there physically is a way to not only connect with other individuals with disabilities, but also show people without disabilities that, "Hey, we can still do a lot of things. I climb more now, and I've climbed more after my injury than I ever did before my injury."

Peter Poullos:

Like rock climb?

Hammad Aslam:

Yeah, rock climb. (laughs) Yeah.

Peter Poullos:

You can pull your whole body up with your arms without using your legs at all?

Hammad Aslam:

Yeah. Yeah.

Peter Poullos:

Wow.

Hammad Aslam:

... as I said, I used to really like weightlifting before my injury. So I guess it came in handy.

Peter Poullos:

How do you think being a person of color impacts your experience as a disabled person? What is the intersection like?

Hammad Aslam:

The intersectionality as an individual with disability and as someone of color, someone from another country, especially a South Asian country, someone with Muslim name, you know, it prevented me from really accepting my injury, I feel like early after my accident, because I didn't know anyone at the time who had a disability. My life had completely changed because I just didn't know anyone with a disability. And I hadn't seen anyone. There wasn't much representation.

And so, that made it harder in that. But however, it allows me now to connect with people who are from South Asia, who are from East Asia, who have a different cultural background. Having a different cultural background also, it would seem like it would be a hindrance in connecting with people, different cultural backgrounds from me. But however, as we talked about earlier, having the disability really levels the playing field and it allows me to connect with people, even though everything else is different about us.

Peter Poullos:

How does the Pakistani community view people with disabilities?

Hammad Aslam:

I don't want to make too broad of a generalization. I feel like it's just like anyone who hasn't seen someone with a disability doing a lot of things. I feel like the community may see someone like me as someone who can't become a doctor or be married or have children, or do all the things that I've accomplished. They may seem even more extraordinary, which is limiting. And I feel like it would have limited me if I didn't have a very supportive family and support system. My friends who never treated me any differently, even though I may have been looked at differently by others.

Peter Poullos:

What about being Muslim and having a disability? Are there any special considerations or issues around that?

Hammad Aslam:

No, not in particular. The only thing (laughs) that I always find strange is that when we enter the mosque, people will take off their shoes. For me, what am I going to do? Take off my tires, you know? And so, it's just weird, roll right in. I've actually had one person, the door was heavy, so he helped open the door for me. He helped me inside the mosque and then he took off my shoes and I was like, "Uh, thank you. But you know that, that, that, that does nothing, right? Like, the point of taking off your shoes is so you don't soil the ground where people pray. You know, if you take off my shoes, my shoes are perfectly clean. I've never walked, (laughs) but okay. If that makes you feel better, (laughing) you know, go ahead and take them off."

Peter Poullos:

That is one benefit of paralysis is that you don't wear out your shoes as fast.

Hammad Aslam:

Exactly, yeah (laughs).

Peter Poullos:

You save money on shoes.

Hammad Aslam:

Oh, no doubt. Yeah. (laughs)

Peter Poullos:

What about the culture of the south and disability? Are there any special considerations being disabled in Georgia versus disabled in California?

Hammad Aslam:

No. Actually, there's huge representation down here, I guess, because we have the Shepherd Center in Atlanta. When I was doing my residency in Birmingham, there was the Lakeshore Foundation there. Of course, California has got Santa Clara Valley and the very large VA system there.

I feel like there will always be very open-minded individuals when it comes to people with disabilities. There will always be close-minded people, no matter where you go. But there will also always be a community. There's huge community here of individual with disabilities that I can connect with as well as in California and pretty much everywhere. The south, it gets a bad rep from the northerners, the west coasters. But I love the south. (laughs)

Peter Poullos:

What would you say to people with disabilities who want to be doctors? Do you have any advice for them?

Hammad Aslam:

Yeah. If there's an individual with a disability and wants to be a doctor, I feel, of course, connecting with the mentor is important. There are now many individuals with disabilities who are physicians. So I feel like connecting with someone else who you know who is a physician is very important. In addition to that, just don't be like me. Don't be afraid. Don't be anxious about it. Everyone in medical school, your peers, your faculty members, the other physicians, they're all on your side.

Peter Poullos:

Well, I have to say, it was a real pleasure speaking with you this morning. I think that this conversation is going to be of great interest to our pre-medical and medical students. And I just thank you for being so open and honest with your experience as a physician with disabilities. And I hope that we can work together in the future to promote getting more people with disabilities into medicine.

Hammad Aslam:

Absolutely. It's my pleasure. I really enjoyed talking to you. And if anyone wants to reach out to me, they can. I guess the best way you just reach me on Twitter. My Twitter handle is @HammadAslamMD. So that's H-A-M-M-A-D A-S-L-A-M MD.

Peter Poullos:

All right. Cool. All right, well, have a good rest of your day. Thanks for your time.

Sofia Schlozman: (Narration)

To our guest Dr. Aslam, thank you for so candidly sharing your experiences and your valuable insights with our audience. In your interview, you discussed the importance of representation and creating opportunities to see individuals with disabilities in diverse spaces. I have no doubt that the stories you shared here will create a powerful and hopeful image for many prospective healthcare workers in our audience. To our audience, thank you so much for joining us for this episode. We hope you enjoyed our conversation with Dr. Aslam, and we hope you will subscribe to our podcast and tune in next time.

This podcast is a production of the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus Summit program, the Stanford Medicine, Stanford Medical Abilities Coalition, and the University of Michigan Medical School Department of Family Medicine - MDisability initiative.

The opinions on this podcast do not necessarily reflect those of their respective institutions. It is released under creative commons attribution, non-commercial, non-derivative license. This episode was produced by Peter Poullos, Gillian Kumagai, Lisa Meeks, and Sofia Schlozman with support from the Stanford Medicine Department of Radiology and our audio editor, Amy Hu.

Music Attributions:

-

"Aspire" by Scott Holmes

-

"Donnalee" by Blue Dot Sessions

-

"An Oddly Formal Dance" by Blue Dot Sessions

-

"Lover's Hollow" by Blue Dot Sessions

-

"In Paler Skies" by Blue Dot Sessions

-

"True Blue Sky" by Blue Dot Sessions