From Neurology Today:

Exploring the Exposome, Researchers Parse Out Environmental Triggers of Neurodegenerative Disease

By Jamie Talan

April 4, 2024

Article In Brief

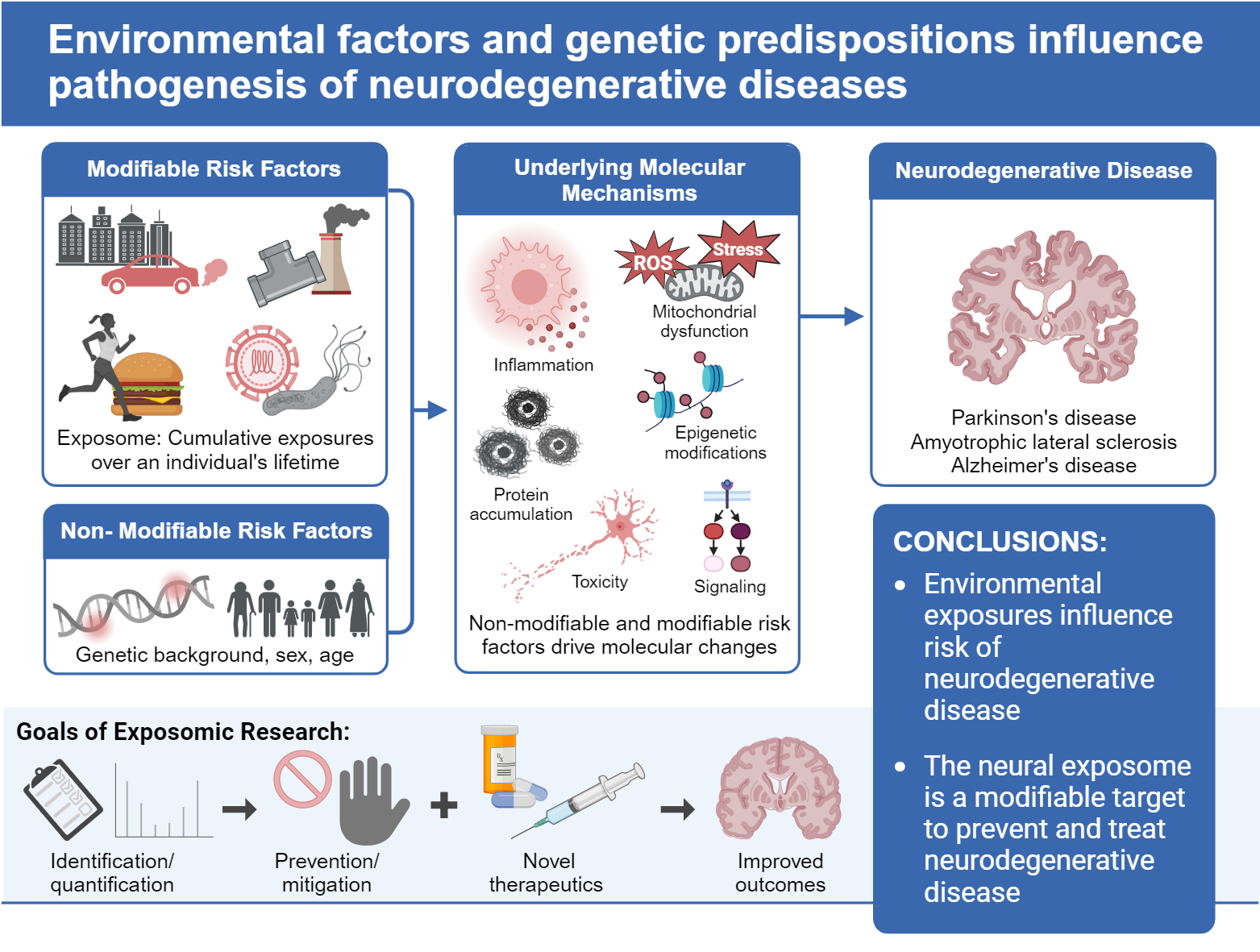

Air pollution, chemical additives in foods, and environmental toxins from exposures from manufacturing and agriculture are associated with increased risk for certain neurodegenerative conditions, including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurologists are studying the exposome to better understand the role these environmental exposures play in the development of these illnesses.

Eva Feldman, MD, PhD, FAAN, traces her nascent search to understand environmental triggers of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) to a boat dock in Port Heron, MI, some 15 years ago. Dr. Feldman, an endowed distinguished university professor and professor of neurology at Michigan Medicine and the University of Michigan, did what had always come naturally to her when taking a history: she got to know her patients.

Several of her male patients shared a passion for boating on the St. Clair River. Their crafts were docked at the same marina. She didn't know what it had to do with their disease, but she remembers adding it to their charts. A few years later, she diagnosed a wife, and then her husband, with ALS. She asked about any shared environmental exposures, and none came to mind. But then the wife said, “But we have known one another since we were kids. We grew up in the same neighborhood.”

She met with another couple with a dual diagnosis, and they had also lived in that same geographical area. The mysterious patterns have turned into a lifetime of study for Dr. Feldman.

Dr. Feldman and a growing number of scientists are now igniting a much-needed effort to understand environmental exposures and how they affect the brain and trigger diseases.

“While it is really important to identify genetic risk factors, genes only explain part of the risk,” said Dr. Feldman, whose latest paper on the neural exposome—all types of environmental exposures being linked to neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer's disease (AD) and Parkinson's disease (PD) as well as ALS—appears in the Feb. 27 edition of Annals of Neurology.

“Even if genetic risk factors exist—and they do—how do toxins, air pollutants, and other lifetime exposures contribute to neurodegenerative conditions?” Dr. Feldman asked. “It's complicated, but it is time that we figure it out and do something to reduce our risk.”

An Overview of the Latest Data

The new paper outlines the latest data, including research on how certain environmental exposures are thought to work on disrupting specific types of brain cells in AD, PD, and ALS. “These diseases are on the rise, and we are trying to identify factors that we may be able to do something about,” Dr. Feldman said.

Her lab just received funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for a prospective study of environmental exposures among production workers. They will enroll men and women in occupations that carry a risk from toxic exposures and follow them over time to see if they have a higher risk for ALS. Her earlier work has shown this to be the case. There is a higher risk among welders, machinists, assembly workers, and people performing certain jobs in the military. She hopes they can follow this cohort of volunteers for a decade or two.

Their work on environmental exposure and its role in ALS has led to seminal findings. She and Stuart Batterman, PhD, professor in environmental health sciences at the University of Michigan, created a 30-page survey that they use in their studies to understand what they refer to as a detailed personal exposome profile—the person's lifelong story of where they grew up, exposures during childhood and beyond, occupation, and hobbies.

In a 2016 study in JAMA Neurology, Dr. Feldman and colleagues measured 122 pesticides and other persistent organic pollutants in the blood of ALS patients and controls. They found a clear increase in levels of many of these compounds in the blood of ALS patients.

They replicated the study last year with another cohort of patients, reporting in the journal Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis & Frontotemporal Degeneration an association between certain occupations and ALS, with a higher rate of illness among production workers. That is why they wrote a grant application for a prospective study.

Dr. Feldman noted that air pollution, chemical additives used in foods, environmental exposures from manufacturing and agriculture, power generation, emissions, and almost everything in our lives may be associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Other factors are associated with risk, including diet, exercise, stressors, and the organisms that live naturally in the body, our microbiome.

“We must understand these varied and multiple environmental exposures and their relationship to neurodegeneration. Once we know, we can figure out ways to prevent these diseases,” said Dr. Feldman. “We need to clean up our environment so we don't put ourselves at greater risk.”

Scientists have known for decades about pesticides and other chemicals that can increase the risk of PD, which has doubled in prevalence between 1990 and 2015, the scientists wrote in the Annals of Neurology review. For example, Samuel Goldman, MD, MPH, and his colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco, studied Marines based in Camp Lejeune between 1975 and 1985, where the drinking water was contaminated with trichloroethylene, tetrachloroethylene, and multiple other volatile organic compounds. They found that the Marines at Camp Lejeune had a 70 percent higher risk of PD than Marines living on a base with clean water.

Now, there are more sensitive tools to determine the mechanisms and figure out ways to prevent these exposures, Dr. Feldman said. More environmental risk factors are also being linked to ALS and AD. Higher rates have been observed in both these conditions. This exploration into the exposome takes into account the gene-environment interaction. She added that genes and their expression, and how they are linked to the exposome, are key to understanding and eventually protecting against these diseases.

Several other exposome projects are underway, including the Human Early-Life Exposome (HELIX) and the European Human Biomonitoring Initiative (HBM4EU), which use mass spectrometry on biological samples. The review provides a detailed rundown of the findings from the last five years and what efforts are needed to drive more research.

David Jett, PhD, director of the Office of Neural Exposome and Toxicology (ONETOX) at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), spent his career studying the effects of pesticides and chemical agents on the human nervous system. When he joined NINDS in 2000, he was primed to lead the NIH Countermeasures Against Chemical Threat program, established after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. His job was to develop drugs and diagnostic tools for victims of chemical exposures during an emergency.

Over the years, he approached his NIH colleagues to consider funding for the neural exposome. His persistence paid off. ONETOX was implemented two years ago and has initiated many funding opportunities.

“We know that genetics alone can't explain most risk factors,” said Dr. Jett. “We have the tools, and it's time to understand the endogenous, exogenous, and behavioral factors that contribute to the environmental threats to the brain. We must determine which risk factors are associated with these illnesses and whether they are causative. Then we can think about interventions. These genetic and environmental interactions are complex, but we've got to start somewhere. If we said it couldn't happen, it never will.”

Caroline Tanner, MD, PhD, FAAN, professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco, Weill Institute for Neurosciences, has spent her career caring for patients with PD. She was a fellow at Rush University Medical Center in the early 1980s when Stanford University's J. William Langston, MD, identified a young man with rapid development of parkinsonism and catatonia and, in succession, five others with identical symptoms. Upon further investigation, he identified the association: synthetic heroin tainted with the toxic chemical MPTP.

“The finding fascinated me,” said Dr. Tanner, who then earned a doctorate in public health and epidemiology. She went on to study many environmental exposures, including water contaminated with solvents at Camp Lejeune. She was the senior author of the 2023 study in JAMA Neurology about the Marines who developed PD years after exposure to the water.

“It's hard to measure exposure in people. It changes over time, and most people don't even know what they were exposed to,” said Dr. Tanner. “We take detailed histories that include what jobs people held, what their job tasks were, where they lived, and whether they came in contact with pesticides and other chemicals. Then we can work with experts to determine what toxicant exposures people may have had over their lifetimes.”

California's state laws make identifying some exposures easier. Reporting laws for pesticide use began in the 1970s. Researchers can examine a person's geographic history acre by acre to see whether they were exposed. As of July 2018, California has made it mandatory for doctors to report new diagnoses of PD to the California Department of Public Health to be entered into a registry.

Dr. Tanner has learned over decades of research that people wearing protective equipment when working around pesticides and other toxic products can mitigate the increased risk of PD. She explained that volatile compounds, such as the contaminants at Camp Lejeune, can evaporate and concentrate in buildings. This may be another way that people are exposed to toxicants.

“There is a lot to be done to reduce the use of toxic compounds,” Dr. Tanner said.

Dr. Tanner was a coauthor of a study led by researchers at the University of Rochester that found a cluster of attorneys who developed PD and certain cancers. They worked in a building next to a site contaminated with dry-cleaning chemicals—including trichloroethylene, which was also found in Camp Lejeune's water. Of 79 lawyers, four developed PD and 15 others various cancers.

Ray Dorsey, MD, an endowed professor of neurology at the University of Rochester's Center for Health and Technology, was the first author of that study, published in the journal Movement Disorders on Feb. 23.

“We believe that Parkinson's is a man-made disease,” Dr. Dorsey told Neurology Today. “That means that Parkinson's is likely preventable.”

Dr. Dorsey and three other neurologists highlighted strategies to address harmful pesticides in PD among other environmental contaminants in a book, Ending Parkinson's Disease: A Prescription for Action, published in 2020. They have organized a symposium, which will take place May 20 in Washington, DC, to address the latest findings on environmental exposures and the brain.

Drs. Tanner and Dorsey highlighted the need for advocacy in this area. “The Environmental Protection Agency [EPA] continues to say that paraquat, used as an herbicide, is safe,” Dr. Tanner said, “which has been rebutted by many studies and more than 50 countries have banned its use.”

“The EPA's decision on allowing paraquat to be used in our country is disappointing,” added Dr. Dorsey.

The EPA is now reconsidering its stand on paraquat, accepting public comments for another month, and will decide whether to ban its use in the United States.

The researchers studying the neural exposome hope more investigation in this area will build greater awareness about potential environmental hazards and lead to more tools to prevent PD, among other neurodegenerative diseases.