In the area of autoimmune and nerve disorders, people usually think of CIDP (chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy) or Guillain-Barre syndrome. However, there is another autoimmune neuropathy that often goes undiagnosed or mischaracterized as CIDP, called Anti-MAG (myelin-associated-glycoprotein) neuropathy.

"Anti-MAG (neuropathy) is not routinely thought about, because CIDP is much better recognized and usually diagnosed first," explains Amro Stino, M.D., director of the University of Michigan's Peripheral Nerve Center. "Anti-MAG neuropathy is misdiagnosed and underdiagnosed quite often, because on first glance it can look quite similar to CIDP and unless someone is thinking about it, they won't check for it."

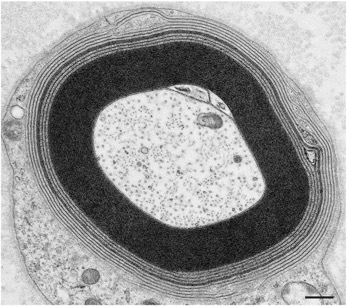

In most autoimmune neuropathies, the degradation of the peripheral nerves is caused by the patient’s own body attacking its own cells. In Anti-MAG neuropathy, the body's immune system develops antibodies against myelin-associated-glycoprotein, which is essential for myelin, the protective sheaths around the nerves. The NeuroNetwork has found myelin to be important for the supply of energy to the nerve. This "attack" results in the myelin around nerves to unravel, causing electrical signals through the nerves to slow down or even become lost. Anti-MAG neuropathy also differs from CIDP in that it is a paraproteinemic neuropathy, meaning that the disorder originates in the bone marrow, which produces too much of the monoclonal antibody that attacks the nerves.

What does this mean for patients?

Anti-MAG neuropathy, which usually afflicts patients in their 60s or 70s, is twice more likely to happen to males than females. This neuropathy presents itself in the hands and feet: gait unsteadiness and instability, numbness in the hands and feet, or even "foot drops." Together, these symptoms make it a significant source of fall risk to the elderly patients who suffer from it.

Even though anti-MAG is often misdiagnosed as CIDP, it does not respond to typical CIDP treatments. It only partially responds to a drug called rituximab in 30%-50% of patients, which acts like chemotherapy by depleting circulating B-cells in the blood.

One of the reasons it has been difficult for researchers to identify possible interventions for Anti-MAG is the variability in patients and the need for verified bedside tests or measurements of the neuropathy, which is not the case in CIDP. Dr. Stino is part of an international natural history study to develop those improved measures of disease activity.

Regarding future treatment options, Dr. Stino completed an investigation evaluating an immunomodulatory cancer drug called Lenalidomide. Others are exploring B-cell-depleting medications that are more potent than Rituximab. In addition, researchers in Italy and at other centers are looking at a class of drugs called Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors. There is a subset of Anti-MAG sufferers with a specific gene mutation, and this new treatment has the potential to be successful and give hope to these Anti-MAG patients.

In the clinic, Dr. Stino directs the Peripheral Neuropathy Clinic and Autonomic Lab, including leading the treatment of CIDP and helping to make the University of Michigan Health a center of excellence.