If quality improvement in health care is built on a foundation of data, the data had better be sound.

Jill Jakubus, PA-C, MHSA, MS, sought to test the foundation underpinning risk-adjusted benchmarking of trauma centers in the Michigan Trauma Quality Improvement Program (MTQIP)—and determine whether an external validation program could affect the accuracy and reliability of the data.

“Researchers seek to improve care via data. Conducting research with data that’s inaccurate or unreliable holds a real potential of arriving at an incorrect conclusion,” Jakubus said.

The study she authored for The Journal of Trauma and Acute Surgery, along with Dr. Mark Hemmila at Michigan Medicine, determined that the foundation needs continual maintenance to ensure integrity.

Quality improvement begins with a question: How are we doing?

MTQIP, coordinated by the University of Michigan, began in 2008 as a pilot project and is now a formal collaborative quality initiative sponsored by Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan. It includes 35 Level I and II trauma centers in Michigan and Minnesota.

The collaborative’s mission is plain: To improve the quality of care in trauma centers by sharing data and implementing evidence-based practices.

So, how is everyone doing? The data should hold the answers, but that data is collected from people who may interpret things differently, even when there are standard definitions for traumatic injuries and conditions.

“Unlike data collected from a lab, where there’s a single identifiable source, the data that we use is an aggregated dataset from multiple trauma centers. Even though there are standardized data definitions, there’s a chance that people may capture data differently,” Jakubus said.

Apples, oranges, and outcomes

On paper, two different hospitals may appear to have the same outcomes, until you normalize for what people looked like going in. That’s where risk adjustment comes in.

One hospital may tend to see a relatively healthy patient population. Another may tend to see sicker patients. Without adjusting for that, the outcomes won’t be accurate and patients, providers and payers won’t have a clear picture of how care stacks up at different places.

“Do you look like an apple or do you look like an orange? If you don’t capture those variables well, you make somebody appear something they’re not,” Hemmila said.

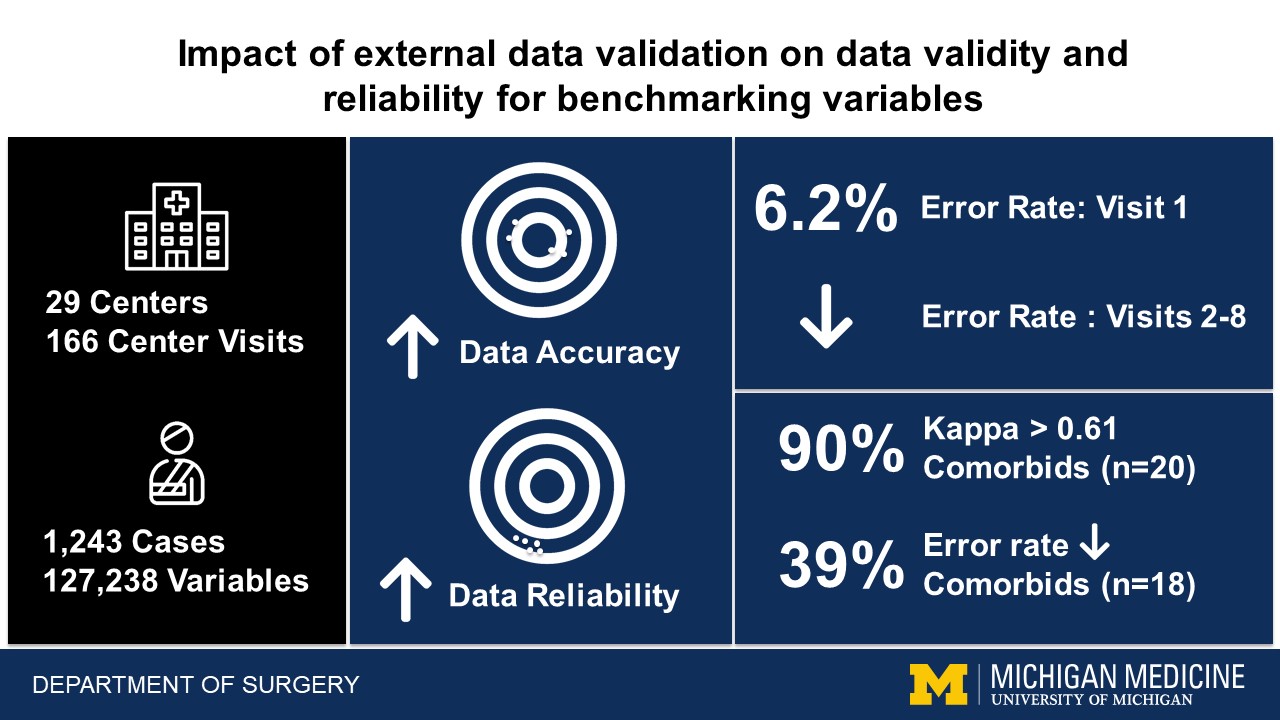

Jakubus and a team conducted annual validation visits from 2010-2018 at the participating centers to review select cases from data shared via a trauma registry. They selected complex cases (those involving blunt or penetrating trauma in people older than 16 with a trauma score higher than five) that might challenge data extractors at the centers, and thus be potentially prone to error. Michigan Medicine’s trauma center was also subject to the validation visits, which were conducted by a qualified alternate registrar.

Same definitions, different conclusions

Trauma scores and injury designations are based on a standard set of definitions, so different systems seeing different patients should still come to consistent conclusions.

What if abrasions are missed in the total score—or the severity of head traumas are perceived differently from one hospital to the next? The validation visits revealed variability like that, with errors of omission being the most common.

“Data abstractors miss external injuries such as bruises, abrasions, and lacerations when they’re scoring. Often that doesn’t add a lot of points in a total injury score, but it makes difference and it translates to issues in risk adjustment modeling,” Jakubus said.

Human validation can correct human error. Error rates improved with each subsequent validation visit during the study, from 6.2 ± 4.7 from the first visit to 3.6 ± 4.3 after the eighth visit.

Still, even with a standard set of definitions, they continually evolve and conversations are ongoing.

“Sometimes death isn’t death. There’s brain death. Is that the death? And there’s absence of cardiac activity. Is that the death? Death can occur at different times. Let’s say a person wants to donate their organs to other patients. These real scenarios represent nuances that have to be consistently accounted for.” Jakubus said.

It’s not personal, it’s data

The validation visits were an exercise in discovery, diplomacy and sensitivity.

Validators fielded skepticism from trauma centers when presenting results indicating a problem, and that pushback was often rooted in a belief that a center was different. Navigating that was a valuable lesson for the team.

“One of the things we learned early on is this has the potential to be a very emotional thing. The way we learned to disarm that feeling was to be very objective: ‘Let's look at supporting documentation and let’s look at definitions and walk through that.’ Once we did that it helped promote trust,” Hemmila said.

Jakubus said that skepticism was tempered with training, coaching, and focusing the conversations on finding the truth rather than fault with the data abstractors.

“If the radiologist doesn’t dictate in the medical record that the ribs 5, 6, 7 are broken and it just says simply broken ribs, that changes how abstractors can capture the data. We can feed that opportunity back to the radiologist,” Jakubus said.

The long game and continual maintenance

Quality improvement doesn’t always happen overnight—or even over a year. In this case, it took ten years of data collection and eight years of visits to see trends, evaluate them, and implement a plan for addressing them.

While work like this doesn’t provide the same hit of instant gratification some other work does, it’s essential to the work that’s built on it, Hemmila said.

“This is a huge effort in terms of time and people and money. It’s not easy. The easy thing is to say it will all be OK without looking. This does matter. It’s a slow long slog but if you don’t do it you don’t have a solid foundation.”

The duration of the study was long, but the work isn’t done. What it revealed was that continuous maintenance is essential to the integrity of the system.

“This thing is like a sand castle. You can build it once and if you expect it to stay intact, that’s an illusion. If you want that sand castle to stay intact, you have to work on it every day. Quality improvement is like that,” Hemmila said.