Education News & Stories

News to Empower. Stories to Inspire.

Celebrate an incredible research discovery. Follow a learner on their path through a U-M Medical School program. Discover news that shapes the future of health care.

Medical School News

Paul Picton, M.B., Ch.B., MRCP, FRCA, has been appointed interim chair of the Department of Anesthesiology in the Medical School, effective May 1. The provost has provided interim approval of his appointment, and it will be reported at the May Board of Regents meeting

Medical School News

Four with Medical School ties are among 12 University of Michigan faculty and staff members recognized by the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) as 2023 fellows in recognition of their extraordinary achievements.

Medical School News

Four faculty and two staff members from the departments of Anesthesiology, Neurology, Radiology and Surgery, and the Office of Graduate Medical Education (GME), are recipients of GME Awards for 2024

Medical School News

The Medical School will showcase ongoing efforts to achieve carbon neutrality by hosting activities that coincide with Earth Day on April 22, as well as Earth Week from April 22-26.

Medical School News

Eric S. Holmboe, M.D., president and chief executive officer for Intealth, will deliver the James O. Woolliscroft, M.D. Endowed Lecture in Medical Education from 5-6 p.m. on April 30 in the Danto Auditorium of the Frankel Cardiovascular Center. The Grand Rounds presentation is open to the entire Michigan Medicine community, as well as faculty, staff and learners from the U-M’s other health sciences schools

Medical School News

There are many intriguing aspects to the honor of a faculty member holding a named professorship in the University of Michigan Medical School: the excitement of receiving one of the highest honors the U-M can bestow on a faculty member; an understanding of the rich history of the person(s) for whom their professorship is named; and the flexibility of what the professorship allows the holders to do during their career. On April 1, the Medical School hosted a celebration of faculty who were appointed to named professorships in 2023.

Medical School News

Paul Picton, M.B., Ch.B., MRCP, FRCA, has been appointed interim chair of the Department of Anesthesiology in the Medical School, effective May 1. The provost has provided interim approval of his appointment, and it will be reported at the May Board of Regents meeting

Medical School News

Four with Medical School ties are among 12 University of Michigan faculty and staff members recognized by the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) as 2023 fellows in recognition of their extraordinary achievements.

Medical School News

The Medical School will showcase ongoing efforts to achieve carbon neutrality by hosting activities that coincide with Earth Day on April 22, as well as Earth Week from April 22-26.

Medical School News

Four faculty and two staff members from the departments of Anesthesiology, Neurology, Radiology and Surgery, and the Office of Graduate Medical Education (GME), are recipients of GME Awards for 2024

Medical School News

Eric S. Holmboe, M.D., president and chief executive officer for Intealth, will deliver the James O. Woolliscroft, M.D. Endowed Lecture in Medical Education from 5-6 p.m. on April 30 in the Danto Auditorium of the Frankel Cardiovascular Center. The Grand Rounds presentation is open to the entire Michigan Medicine community, as well as faculty, staff and learners from the U-M’s other health sciences schools

Medical School News

There are many intriguing aspects to the honor of a faculty member holding a named professorship in the University of Michigan Medical School: the excitement of receiving one of the highest honors the U-M can bestow on a faculty member; an understanding of the rich history of the person(s) for whom their professorship is named; and the flexibility of what the professorship allows the holders to do during their career. On April 1, the Medical School hosted a celebration of faculty who were appointed to named professorships in 2023.

Points of Blue

Anita Valanju Shelgikar (she/her/hers), MD, MHPE, is a professor of neurology at the University of Michigan Medical School and the director of the sleep medicine fellowship at Michigan Medicine.

Points of Blue

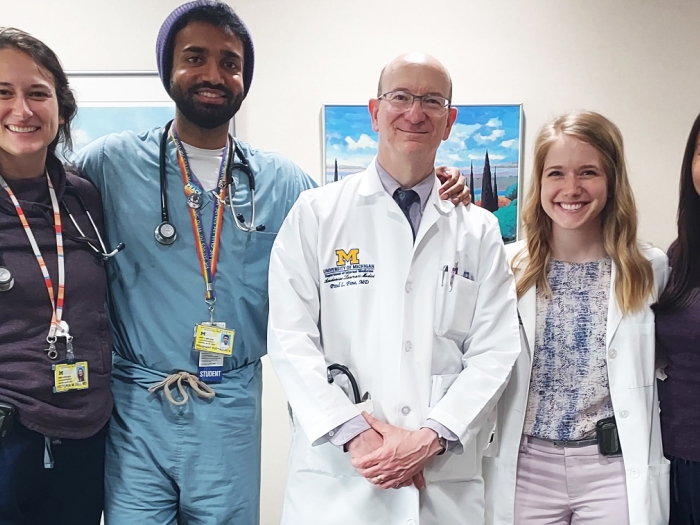

Paul Fine, MD, is a clinical associate professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan Medical School. He earned his medical degree and completed his residency in internal medicine at Michigan Medicine. Here, he shares how he loves to help others, his passion for piano (make sure to check out his music!) and his advice for students.

Points of Blue

Jasmyne Jackson, MD, MBA, is a Pediatric Emergency Medicine Fellow at Brown University and an Emergency Medicine Healthcare Leadership and Administration Fellow at Brown Emergency Medicine.

Points of Blue

Kahli Zietlow, MD, is a clinical assistant professor of internal medicine who specializes in geriatric medicine. Originally from Michigan, she earned her undergraduate degree at the University of Michigan before attending Duke University, where she earned her medical degree and completed her residency and fellowship. Dr. Zietlow returned to U-M in 2020 and is currently the interim director of Interprofessional Education (IPE) at UMMS and the associate program director of the Geriatric Medicine Fellowship. She is passionate about IPE, geriatric medicine and medical education. Read on to learn more about Dr. Zietlow, including her talent as a wildlife photographer!

Points of Blue

Alli Ruff, MD, MHPE is a clinical associate professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan Medical School. Originally from Florida, she came to Michigan after earning her MD from the University of Miami and completing an internal medicine residency at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio. Dr. Ruff loves working with learners at all levels and fills many roles around the medical school. Find out how she faces challenges as a physician and her most important advice for medical students.

Points of Blue

Gabriela Leticia Maica (she/her/ella), pictured far right above, comes from Staten Island, NY.

Health Lab

Experience gave him a new appreciation for interprofessional patient care

Health Lab

Post-traumatic stress worse among Mexican American caregivers compared to white caregivers.

Health Lab Podcast

The device would be the first clinical-grade, diagnostic wrist-worn device for long term Afib monitoring. Visit Health Lab to read the full story.

Health Lab

A physician invents a creative approach for medical students in diabetic care.

Health Lab Podcast

Evidence can help inform fertility care for transgender and gender diverse people who wish to become parents. Visit Health Lab to read the full story

Health Lab

The tool, which is free to use, includes photography, videography and virtual reality learning resources from anatomical donors, along with comprehensive lab manuals and interactive files with click-to-reveal testing capabilities.

NOTICE: Except where otherwise noted, all articles are published under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 license. You are free to copy, distribute, adapt, transmit, or make commercial use of this work as long as you attribute Michigan Medicine as the original creator and include a link to this article.